This viewpoint is part of Foresight Africa 2024.

Africa’s economic outlook has deteriorated since the heady days of “Africa Rising” when Africa grew strongly post-2000—much faster than it had since the commodity boom of the 1960s and 1970s. But African growth is now slowing down.

Economic conditions are tougher; circumstances are less favourable. The global growth which supported Africa’s growth spurt has slowed. Asia, Europe, and the U.S. are looking inwards and are not reliable partners, global value chains are shortening post-pandemic, and new labor-saving technologies threaten to undermine Africa’s advantage of abundant labor. Debt worries in many African economies make them more vulnerable.

The implementation of policies which exploit Africa’s continental synergies is now more important than ever.

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) is steadily being implemented. Agreed in 2018, it came into force in 2019 for the 24 countries which had by then ratified the agreement. Forty-seven of the 54 countries which signed the agreement have now ratified it. Negotiations on details continue while some countries have begun to trade certain products through the Guided Trade Initiative—a piloting program. Driven by a dedicated secretariat, the AfCFTA has a dynamism that no similar continental initiative ever had.

Beyond trade in goods, Africa needs greater personal mobility across national borders, especially for traders, investors, and professional service providers. Indeed, the AfCFTA protocols for trade in services and investment explicitly require such mobility.

Beyond trade in goods, Africa needs greater personal mobility across national borders, especially for traders, investors, and professional service providers.

In the year that the AfCFTA was signed, 32 African leaders signed the African Union Free Movement of Persons Protocol to progressively open African borders for people. But only four countries have ratified the agreement. No ratifications have been registered in Addis Ababa since 2019.

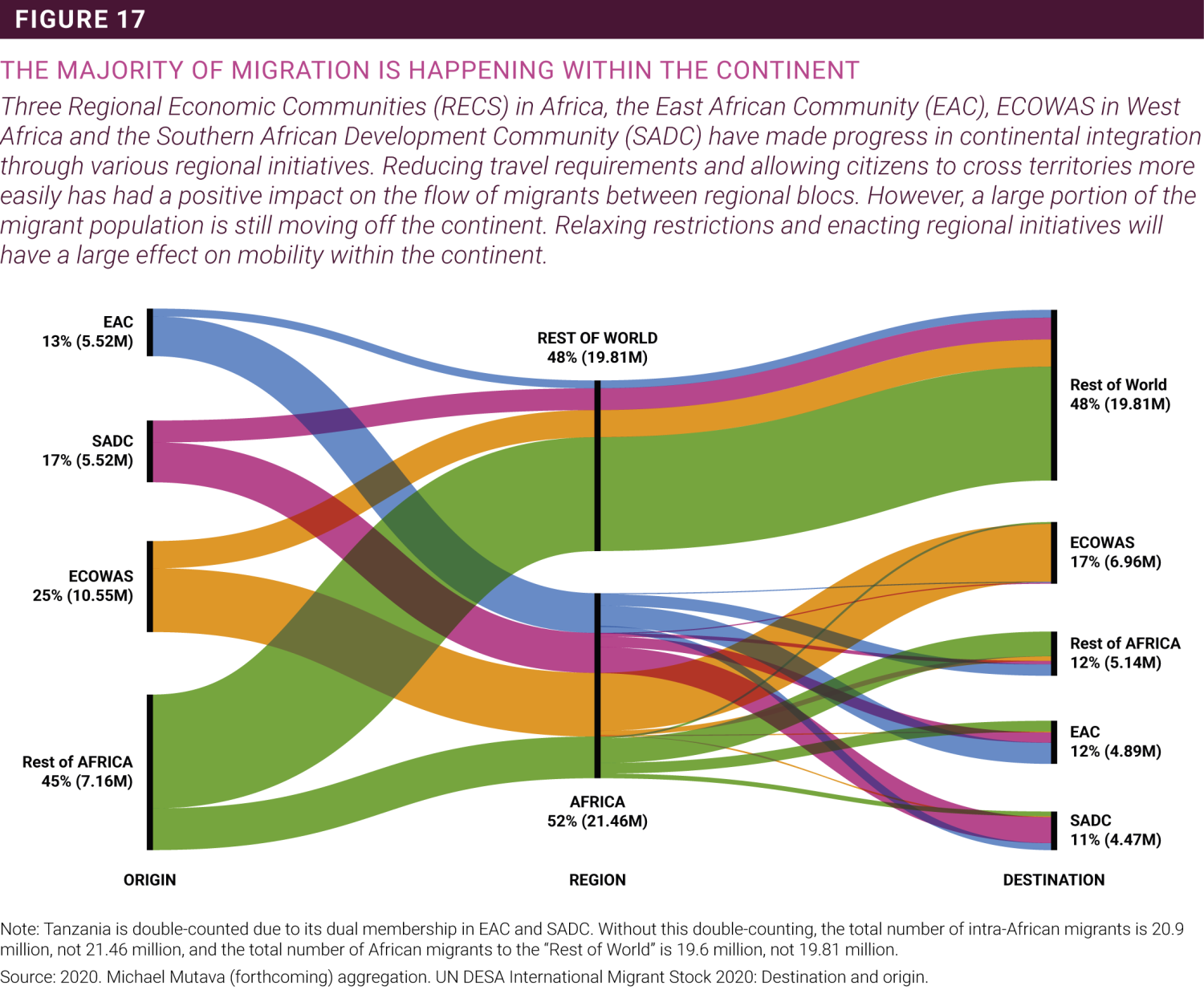

There has been more progress in regional, sub-regional, bilateral, and unilateral initiatives than in the continental process. Regional Economic Communities (RECs) such as the East African Community, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the Southern African Development Community have largely visa-free travel for regional citizens, and subsets of countries within those regions have moved further, only requiring official identity documents. Access to work permits for citizens of fellow REC members has also been improved in some regions in Africa.

Why then is there a lack of enthusiasm for the African Union’s free movement protocol? Some richer countries in Africa, which provide citizens and legal residents with a range of social services and transfers, fear that large groups of economic immigrants might resort to inappropriate strategies to obtain residence. In countries already facing social issues, such as poverty and high unemployment, the issue of immigration can become politically explosive.1

Policymakers in those countries fear the implementation of the African Union Free Movement of Persons Protocol will make them vulnerable to large-scale economic immigration. Though the Protocol does not entail the kind of obligations they fear and contains several safeguards, resistance to a broad continental initiative remains.

Greater mobility through regional, subregional, bilateral, and unilateral reforms should be encouraged. The African Union (AU) should also explore narrowing the continental focus to the mobility of skilled people—traders, investors, professional service providers, and graduate students. Refocusing the AU initiative in this way will allow it to draw on the dynamism of AfCFTA processes for support. It will enable member states to develop practices and systems of documentation and mutual cooperation that in the long run can build trust and enable broader mobility agreements.

The Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN)2 and two overlapping regional blocs in South America progressed by focusing on the mobility of skilled people first.3 In the South American case it laid the basis for broader agreements on mobility.4 Africans can learn from these experiences.

-

Footnotes

- Hirsch, Alan. 2021. The African Union’s Free Movement of Persons Protocol: Why has it faltered and how can its objectives be achieved?, South African Journal of International Affairs, 28:4, 497-517.

- Sugiyarto, Guntur, and Dovelyn Rannveig Agunias. 2014. “A ‘freer’ flow of skilled labour within ASEAN: aspirations, opportunities and challenges in 2015 and beyond.” Issue in Brief. Washington: International Organization for Migration, Migration Policy Institute: 11.

- Brumat, Leiza. 2020. “Four generations of regional policies for the (free) movement of persons in South America (1977– 2016).” Regional integration and migration governance in the Global South. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Arcarazo, Diego Acosta, and Andrew Geddes. 2014. “Transnational diffusion or different models? Regional approaches to migration governance in the European Union and Mercosur.” European Journal of Migration and Law 16.1: 19-44.

Commentary

The whys and hows of the mobility of Africans in Africa

July 17, 2024