This piece was updated on July 23, 2024 with an adjustment to figure 2. Read a newer analysis here.

Since February 2023, the labor force participation rate for prime-age women––those between the ages of 25 and 54––has exceeded its all-time high. As of the most recent jobs report, prime-age women had a labor force participation rate of 77.8 percent. This is remarkable, given evidence that the 2020 recession initially widened the labor force participation gap by gender and by parental status. It is also surprising that these peaks are happening in the summer, as this is typically the season (even after seasonal adjustment) when participation for caregivers is at its lowest.

This analysis explores contemporary trends in prime-age female labor force participation.

After controlling for demographic changes, we find that those who have contributed most to the rebound in overall labor force participation in April and May of 2023, three years after the nadir of pandemic-era participation, are in fact prime-age women. Moreover, among prime-age women and indeed among all groups, women whose youngest child is under the age of five are powering the pack’s upward trajectory.

Overall, growth in participation among mothers with young children since 2020 exceeds other prime-age women when differentiated by the age of one’s youngest child. Among mothers with young children, those who are highly educated, married, or foreign-born are much more likely to be labor force participants today relative to their pre-pandemic peak. And those who are highly educated and married are also much more likely than the average worker to have said that they are continuing to telework at least once a week.

Patterns in prime-age women’s labor force participation

While some of the waxing and waning in participation are the consequence of seasonal and business cycle dynamics, the patterns in female labor force participation have happened over longer timeframes. From the early 1950s through 2000, women’s participation doubled (from about 33 percent to 60 percent) and the aggregate labor force participation rate increased by almost 10 percentage points, driven entirely by women.

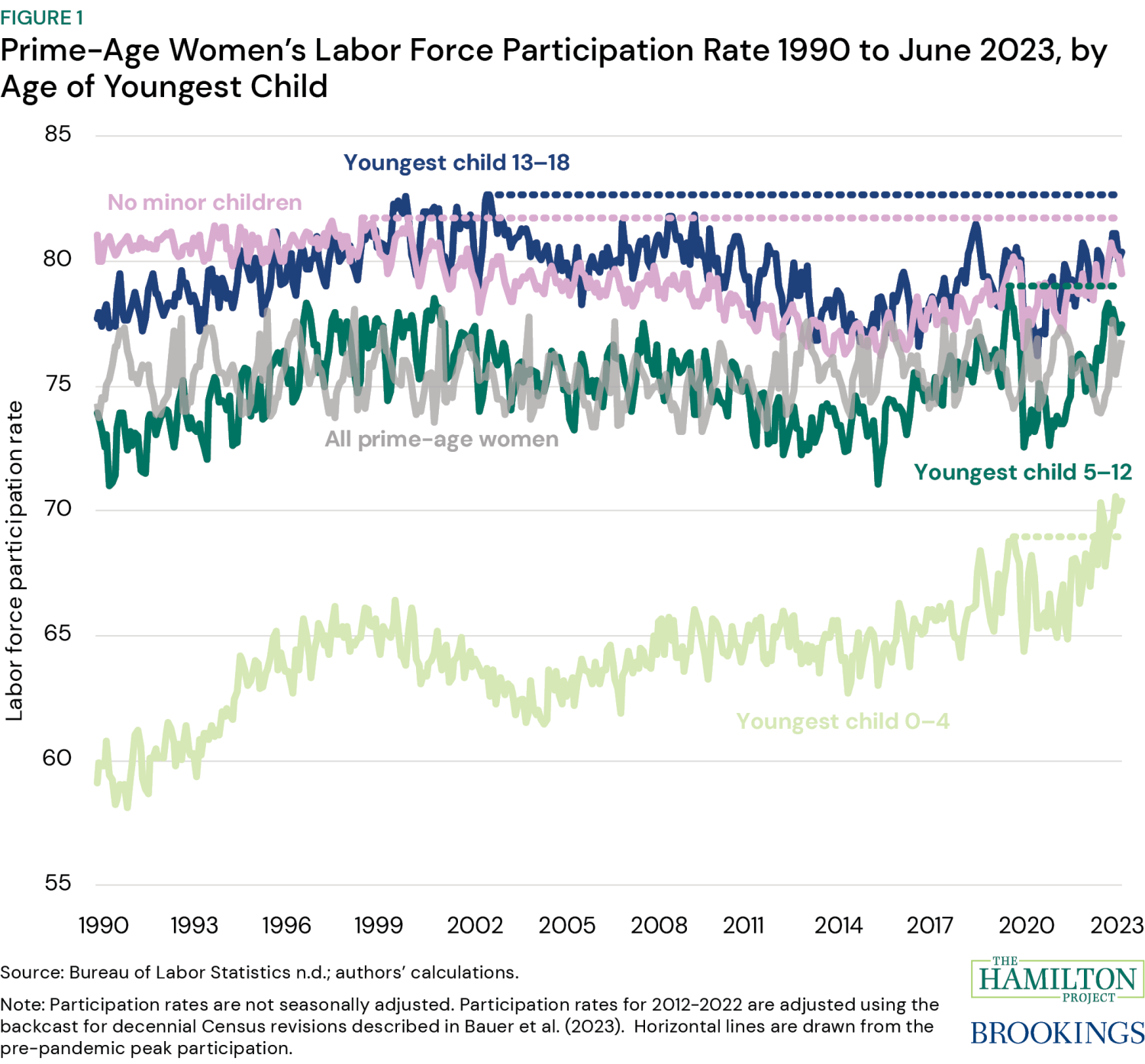

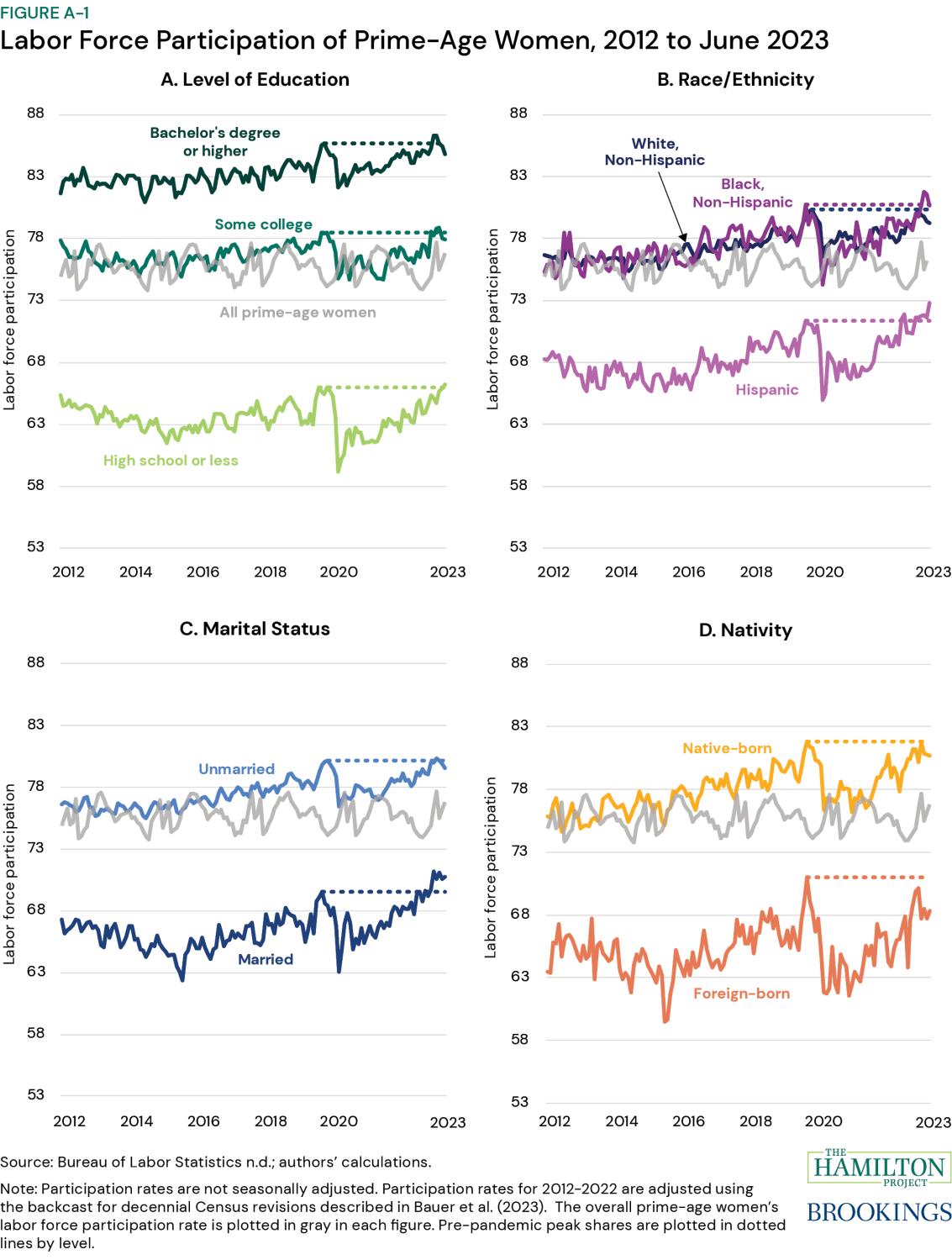

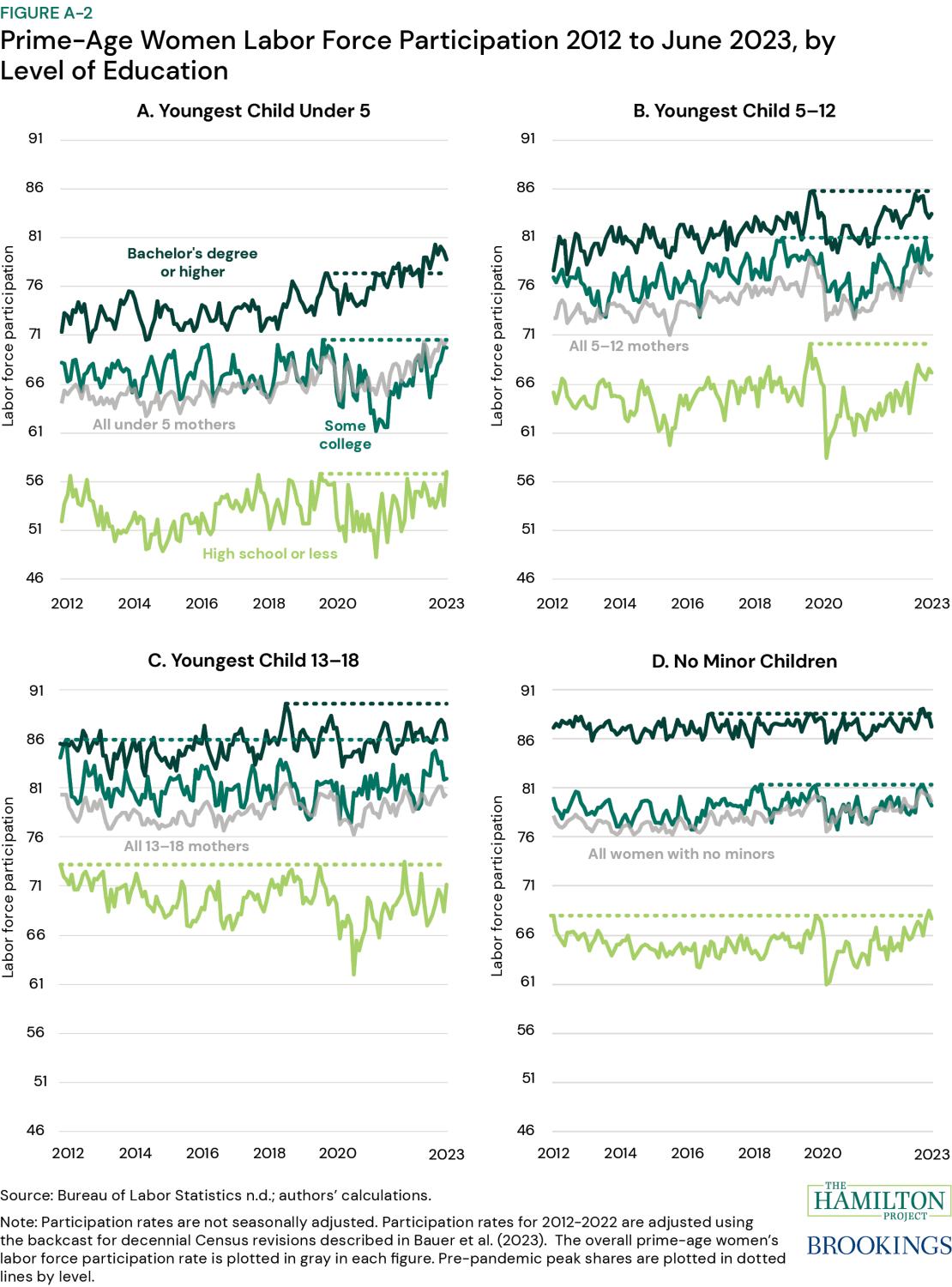

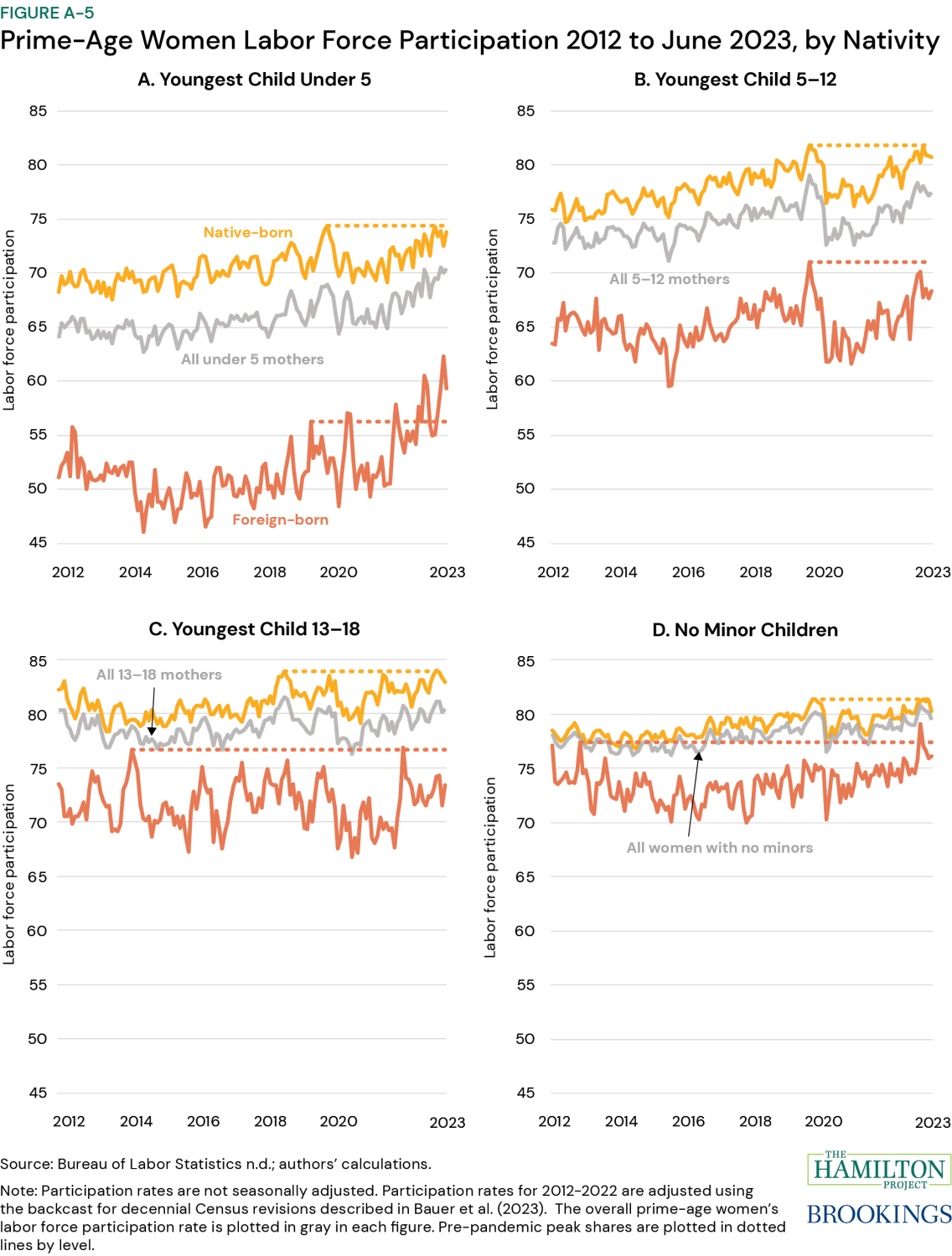

The patterns in labor force participation by the age of one’s youngest child in recent decades are striking. Figure 1 breaks out prime-age women’s labor force participation into those who do not have minor children (most likely to be those prime-age women who are the youngest and oldest within the group), and mothers whose youngest child is under 5, between the ages of 5 and 12, or a teenager. Here and throughout, pre-pandemic peaks are shown as horizontal dotted lines.

Following welfare reform and the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit in 1996, and during the strongest labor market in decades, participation rates accelerated for a time. Since 2000, both prime-age men and women’s participation rates started to decline; around 2015, however, there was some evidence of a rebound. Figure 1 shows that the pandemic halted this progress, but the post-pandemic period has spurred a new rebound for women.

Figure 1 shows that mothers with teenagers and mothers without children at home (either because they do not have children or they no longer have a minor child) have historically had and currently have the highest participation rate. The participation rate of mothers whose youngest was between the ages of 5 and 12 has typically been a few percentage points below but leading into the pandemic was on a path toward convergence. Through March this year, the participation rate of those with children ages 5 to 12 had largely rebounded about 99 percent towards its pre-pandemic peak, although it has fallen slightly since.

Participation rates of women whose youngest child is under 5 have been relatively flat since 2008, though their participation started to pick up too in the mid-2010s. Since then, the participation rate of women with young children (70.4 percent) has exceeded its pre-pandemic peak by more than 1.4 percentage points and has seen the most rapid growth.

The contribution of prime-age women to post-pandemic changes in participation

Changes over time in the overall labor force are primarily driven by two factors: changes in the composition of the population (like population aging or declining immigration) and changes in the propensity of different groups to participate (like teen participation declining as school enrollment increases). While population shifts are less explicitly a matter of policy—immigration aside—the factors that lead to a higher or lower propensity to participate can be affected by policies and economic conditions that make working more or less attractive.

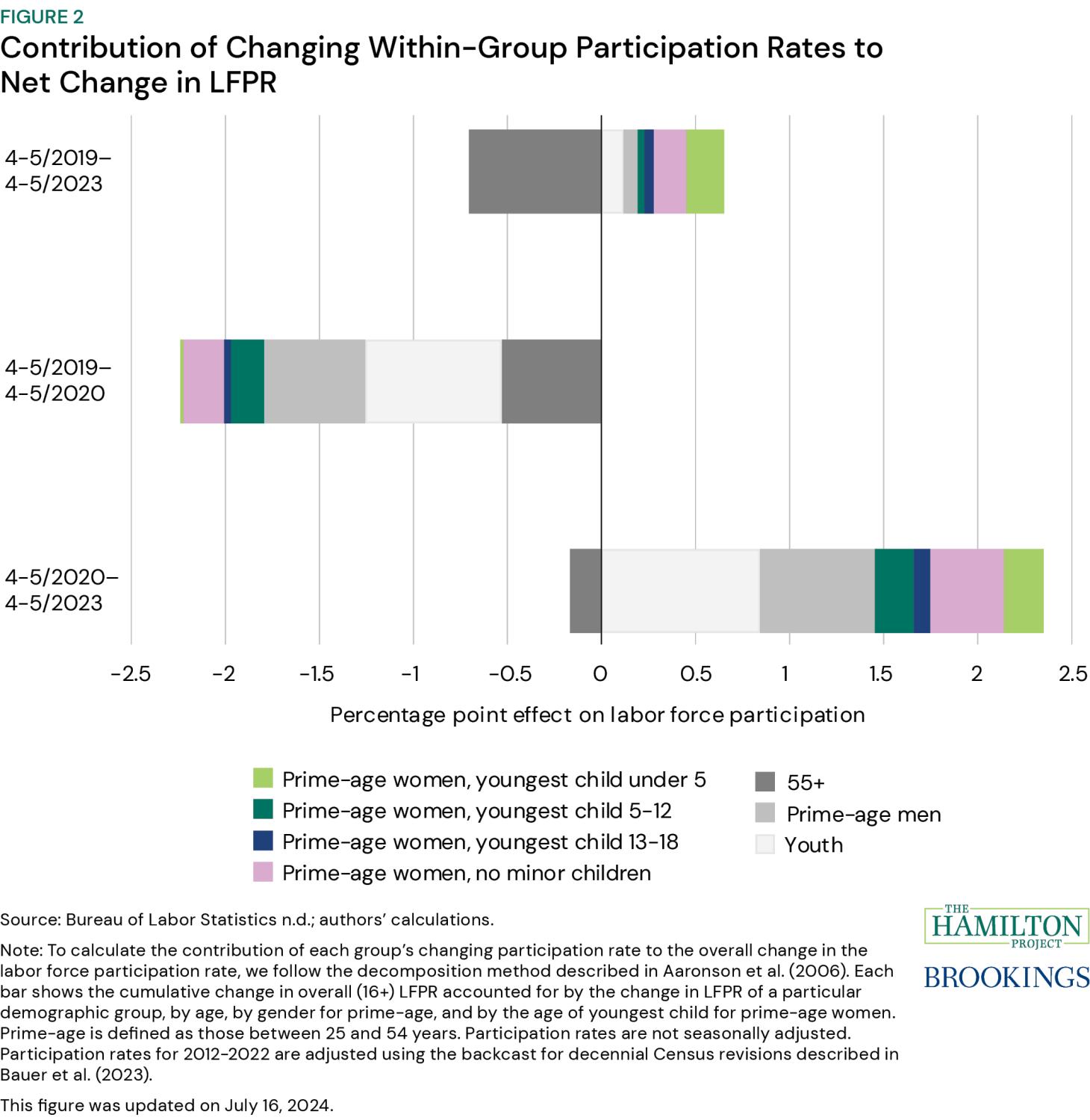

In figure 2, we show the contribution of changing labor force participation rate within different demographic groups to the total change in labor force participation in recent years if we were to hold population-related factors constant. We pool together two months of data for each period (April and May) for increased stability but primarily because these months marked the nadir of participation in 2020. We break the net change into two time periods critical for understanding recent labor force participation dynamics: the labor market collapse (April–May 2019 to April–May 2020) and its recovery (April–May 2020 to April–May 2023).

This analysis shows that the increases in the propensity to work among prime-age women (the non-gray bars) have driven the recovery in aggregate participation, which is consistent with our most recent work. Among prime-age women, mothers whose youngest child is under the age of five have led the pack in terms the net change from the pre-pandemic period to today (0.21 percentage points).

Trends to watch for labor force participation gains among mothers with young children

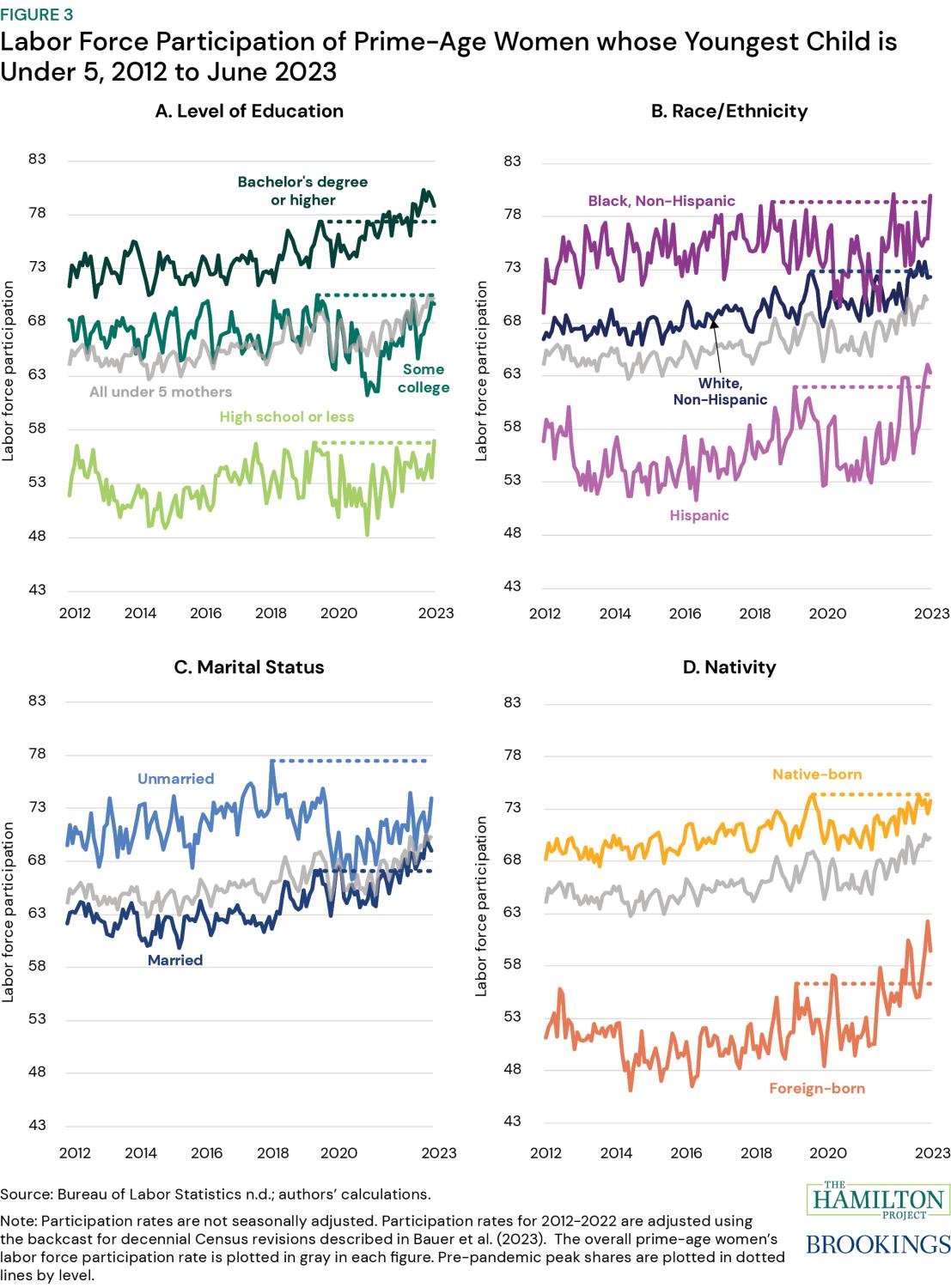

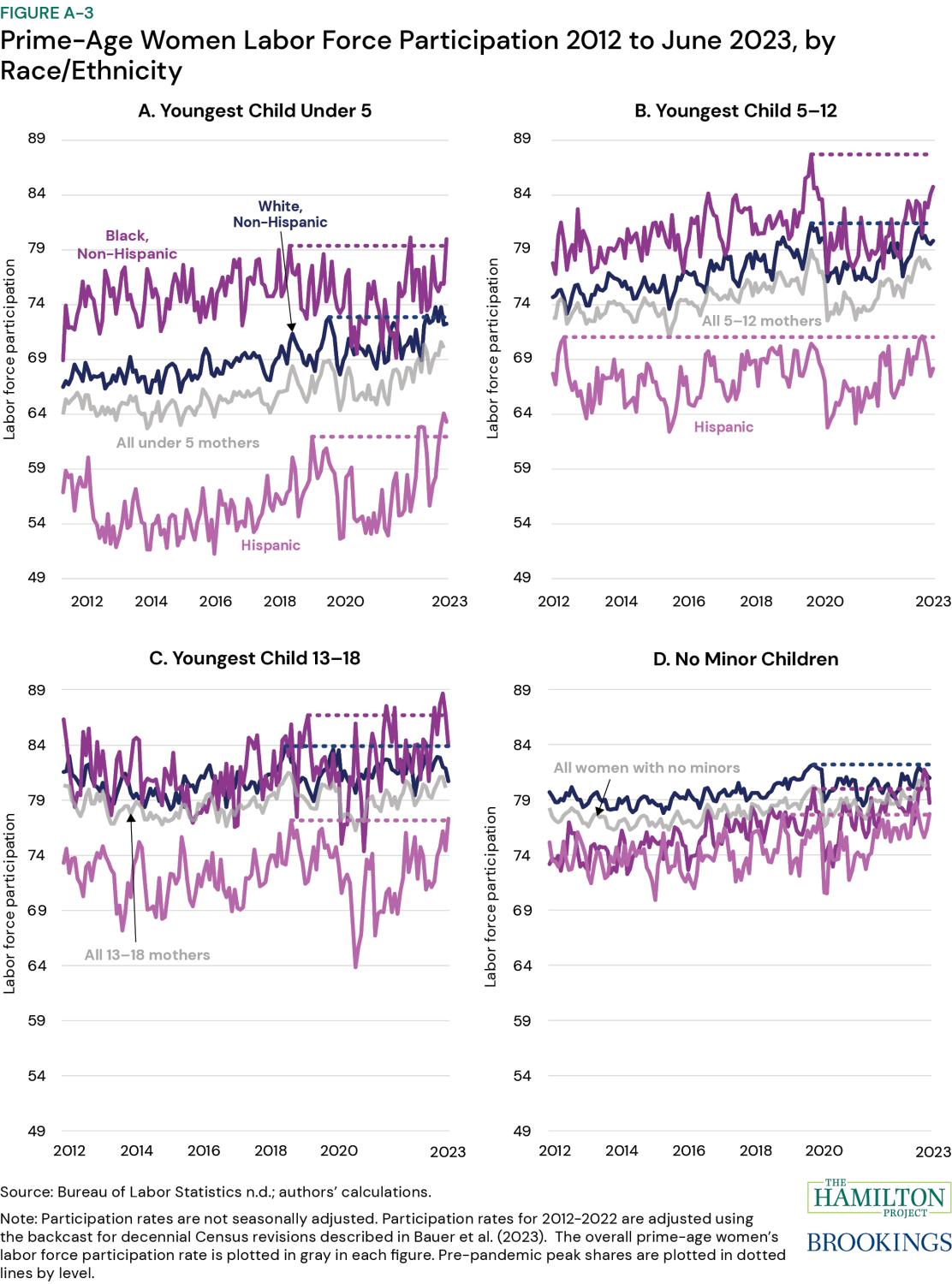

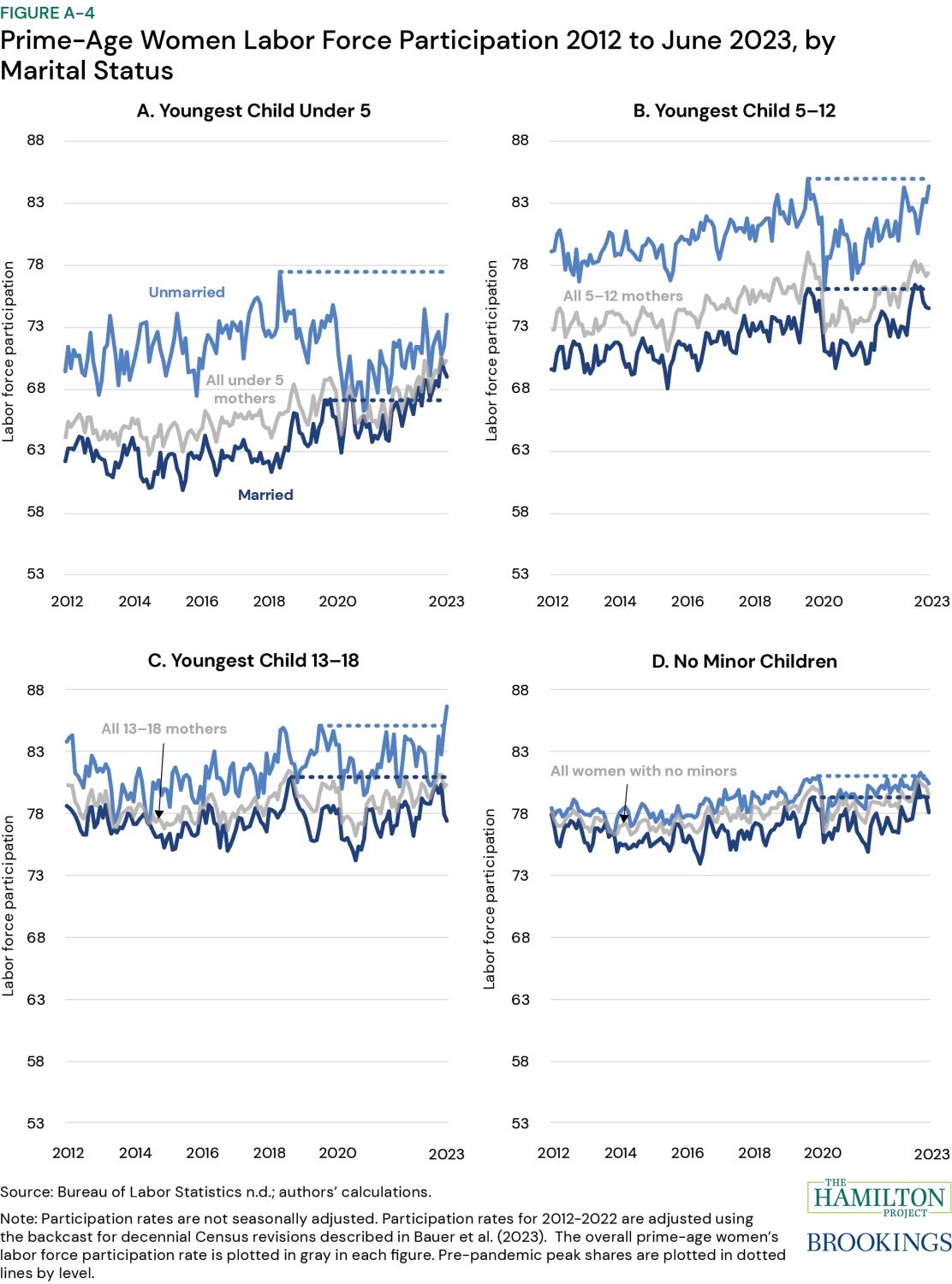

What demographic factors could contribute to the growth in participation shown thus far? Figure 3 shows labor force participation rates for women whose youngest child is under 5 by education, race/ethnicity, marital status, and nativity. We draw particular attention to three groups: women with at least a bachelor’s degree (3a: dark green line), married women (3c: dark blue line), and foreign-born women (3d: orange line).

Labor force participation among mothers with young children who have at least a bachelor’s degree has exceeded its pre-pandemic peak of 77.9 percent since November 2019 and was nearly 3 percentage points above that peak this past April. They and women without children are so far the only groups who across all education levels have generally returned to or exceeded pre-pandemic rates of participation (appendix figure A-2).

Differentiating by marital status for mothers with young children (figure 3-C), we find that the labor force participation rate of married and unmarried mothers with young children is moving toward convergence. From 2016 through 2019, the average labor force participation rate for married women with young children was 63.2 percent and for unmarried women with young children was 72.6 percent. In the first six months of 2023, married women with young children had a labor force participation rate of 69.0 percent, and it was 72.1 percent for those unmarried. This convergence appears to be happening only among mothers with young children (see appendix figure A-4).

Finally, figure 3-D breaks participation rates for mothers with young children by their nativity, (i.e., whether they were born in the U.S. or not). Others have speculated that substantial growth in foreign-born participation has made up for a slower recovery among those who were born in the US. In fact, women with young children who were born outside the U.S. are currently exceeding their pre-pandemic peak participation rate, though foreign-born prime-age women on the whole are not. Foreign-born mothers with at least some college education and those who are Asian are participating substantially more than they were before, perhaps reflecting changes to immigrant work authorization rules that would allow spouses of H-1B holders to hold jobs.

What about telework?

What has changed about and for mothers with young children that could spur both smaller decreases in participation during the pandemic and evident increases in labor force participation, given that in the aggregate women were most affected during the contraction? There are likely many causes that will be studied in the years to come including: a possible turnaround in fertility patterns that would make new moms more likely to be working moms, COVID-related fiscal and health policy that made it more affordable on a host of dimensions to have a young child and work, work-from-home flexibilities that make it easier for mothers to take and keep a job, labor laws that protect pregnant people and those taking family and medical leave, and the fact that the parents who were most affected by changes to the child care context were parents of elementary-school-aged children. And certainly hot labor market conditions don’t hurt.

Here we focus on telework. Many have shown that greater flexibilities made telework more pervasive during the pandemic and have the potential to support women with caregiving responsibilities.

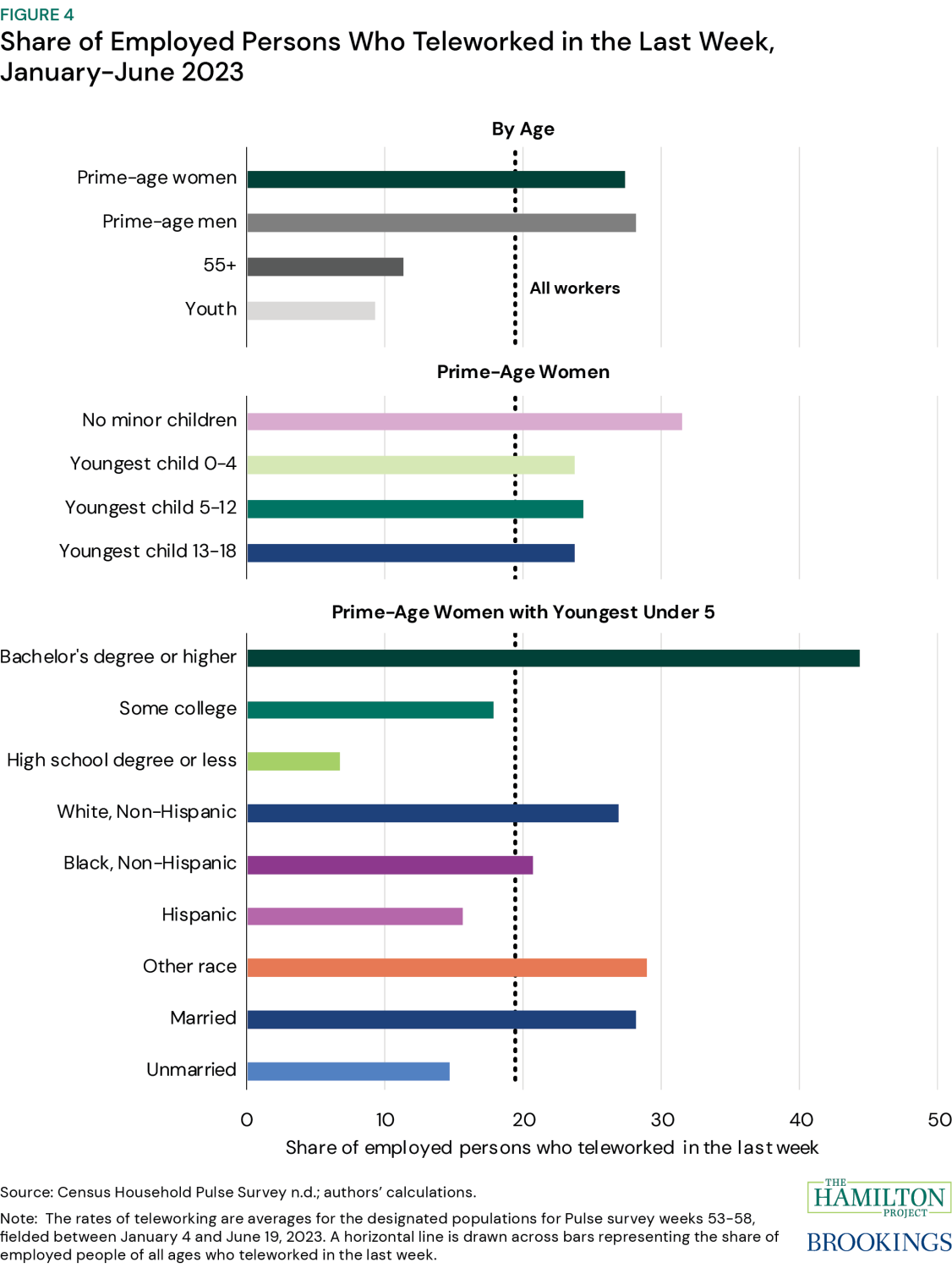

Figure 4 shows the share of those who reported teleworking at least one day last week, averaged for the first 6 months of 2023 of the Census Household Pulse Survey. In these data, just under 20 percent of adults reported working from home at least one day. While we cannot show how telework has changed over time within those Census data, the American Time Use Survey data show that about a quarter of people spent time working at home in 2019 compared with a third in 2022. Doing work at home, as opposed to teleworking, is a much lower standard, so it makes sense that there is a difference between these two measures. But the national average for telework in 2023 is about the same as the share who reported doing any work at home in 2019; it is not a stretch to assume that telework opportunities and take-up have increased.

About a quarter of prime-age women with children, regardless of the age of their youngest child, report working from home in the first half of 2023. Looking just at differences in telework among mothers with young children, figure 4 shows that well-educated women (44 percent) and married women (28 percent) are much more likely than the average worker to say that they are continuing to telework at least once a week.

In short, women with young children who hold at least a BA as well as those who are married have made the most striking gains in pre-pandemic labor force participation and are either by far the most (well-educated women) or among the most (married women) likely to be teleworking in 2023.

Conclusion

Labor force participation among mothers with young children has always been and continues to be lower than those without children or who have older children. Tight labor markets, the changing nature of and compensation for work, evolving norms around working, and the need to work when one’s children are young are all factors that support the empirical fact that mothers with young children’s labor force participation has accelerated in the post-2020 to exceed pre-pandemic levels.

But precious little of this change is likely the consequence of a supportive policy context. More can be done to continue to support women’s labor force participation in the United States.

The U.S. is the only country in the world without a universal paid maternity leave policy. There was a temporary federal paid leave policy for COVID; but before and since, paid leave is not guaranteed. During the pandemic, federal resources were generous but not sufficient to prevent child care center closures; but before, the system already had too few seats and was too expensive.

In 2017, The Hamilton Project published “The 51 Percent: Driving Growth through Women’s Economic Participation” premised in the idea that the U.S. economy’s potential cannot be realized unless women who want to participate in the labor market can do so fully. To spur labor force participation, strengthen work supports, and increase access to high quality affordable child care, The Hamilton Project has offered many proposals to address child care-related challenges (by Elizabeth Cascio, Elizabeth Cascio and Diane Schanzenbach, Bridget Terry Long, Aaron Sojourner and Elizabeth Davis, and James Ziliak) and provide paid leave (by Tanya Byker and Elena Patel, Nicole Maestas, and Christopher Ruhm).

Appendix

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Chloe East, Wendy Edelberg, Kathryn Edwards, Misty Heggeness, and Stephanie Schmit for helpful conversations and excellent comments as well as Eloise Burtis and Olivia Howard for superior research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.