In Chapter 2 of Foresight Africa 2024, our authors tackle the existential climate change crisis.

Essay

The climate crisis: A generational opportunity for Africa

By Vera Songwe, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Global Economy and Development, Brookings Institution

The climate crisis is intensifying, extreme events have become the new normal. The fight against climate must not, however, slide into a long, low-intensity crisis. It is a daunting but not insurmountable challenge. Well-executed and at scale, winning the climate battle is synonymous to winning the battle against poverty. It is in this sense that the battle for our planet is also a battle for the prosperity of all its people.

Each year the destruction to the planet is harsher than the last. In 2021 (the latest year for which consolidated global figures are available) atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases reached new highs. The increase in CO2 from 2020 to 2021 was higher than the average annual growth rate over the last decade. Similarly, the annual increase in methane from 2020 to 2021 was the largest annual increase on record. The year 2022 was either the fifth or the sixth warmest year on record according to six data sets.1

Africa is ground zero of the climate crisis. Over the past 60 years, Africa has recorded a warming trend that has generally been more rapid than the global average, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.2

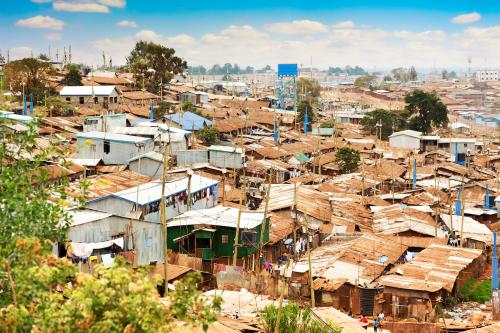

The impact on lives and livelihoods is devastating. Over 110 million people in 2022 were impacted by the climate crisis in Africa.3 Food inflation reached its highest levels in three decades at on average 30%, compounded by the war in Ukraine.4

It is estimated that nearly 282 million people in Africa (about 20% of the population) are undernourished, and suffer from food insecurity on the continent.5 Droughts and flood are worsening agriculture productivity and increasing Africa’s dependence on food imports, worsening the current account balance, and displacing productive investments.

Improvements in livelihoods are correlated with climate events and policies. The response to the climate crisis in Africa broadly calls for a three-pronged approach: Mitigation, adaptation, and nature.

Despite its low emissions levels and favorable initial endowments, Africa must engage on all three fronts. With its increasing population, urbanization, and industrialization, emissions are set to increase in the medium term, but they can be managed and steered toward a progressive transition which delivers growth while protecting our planet.

The paradox of Africa: Africa is energy-access poor, it is renewable energy rich but a large part of its energy comes from coal and other fossil fuels. Of the 1.2 gigatons (Gt) of carbon dioxide emitted in 2020 in Africa, 40% came from fossil fuel-based electricity and heat generation, a quarter from transport and another 17% from productive uses. Closing the energy access gap will require an estimated annual investment of over $25 billion up to 2030.6

In 2022, African countries lost close to $9 billion as a result of loss and damage suffered and spend over 5-15% of their GDP per capita building it back. The loss and damage costs in Africa due to climate change are projected to reach at least USD 290 billion (in a 2 °C warming scenario).78

Africa’s carbon sinks help to slow the speed of global warming and provide a global public good to the planet. A recent study shows that African Tropical forests hold more carbon than previously believed and together sequester more carbon than any other forests in the world.9 26% of land in Africa is classified as forest.10

Illegal logging, poor agriculture, and cooking practices are responsible for the destruction of these vital forests.

Transitioning to a more inclusive green industrial growth agenda offers Africa the best opportunity to accelerate its growth, provide jobs, transform its economies, and build thriving, prosperous societies. Transitioning to the climate economy consistently delivers a higher growth trajectory for African countries. Studies by Vivid Economics, Oxford University, and UNECA for South Africa, DRC, and Egypt in collaboration with the authorities highlight this growth potential.111213 The Automotive Masterplan in South Africa could double employment from 120,000 to 240,000 and increase domestic vehicle production to 1% of global output, of which 20% will be EVs by 2030. These results are similar for Egypt, Senegal, Kenya, and DRC.14

Closing the policy and finance gap

African economies can deliver comprehensive economic programs by designing country-led green, sustainable growth strategies. However, for these policies to be successful they need the right policy environment and adequate financing from both domestic and external sources.

The response to the climate crisis must be global, swift, and at scale. The world needs USD 2.4 trillion per year by 2030, of which USD 1 trillion per year must come from external finance for emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs) other than China to credibly tackle the climate change challenge.15 With the polycrisis from 2020-2023, countries have used up all the fiscal space available to undertake development and investment activity. Increasing debt burdens are also weighing heavily on countries.

Despite increasing costs, financing for climate to Africa is shrinking. It will cost between USD 2.8-3 trillion between 2020 and 2030 to implement Africa’s nationally defined contributions (NDCs). However, total annual climate finance flows in Africa for 2020, domestic and international, were only USD 30 billion, or 12% of the amount needed.16

Climate finance on the continent must be additional, affordable and wealth-creating.

The main financing for climate action will come from three sources: domestic resources, the Multilateral Development Banks and bilateral resources, and the private sector—capital markets, institutional investors.17 Philanthropy is increasingly becoming an important source of resources.

The main financing for climate action will come from three sources: domestic resources, the Multilateral Development Banks and bilateral resources, and the private sector—capital markets, institutional investors.

National governments will continue to fund over half the costs of climate investments. While tax to GDP has increased over the last decade in Africa, the 15.6% average should increase to around 30% to provide governments with the fiscal space required to undertake climate investments at scale.18 There are two ways this can be done. First, phasing out fossil fuel consumption subsidies and second, the rapid development of a market-based, transparent, high-integrity carbon emissions voluntary or compliance trading system. According to studies from the UN Economic Commission for Africa, Africa could raise approximately USD 6 billion in revenue by 2030 and over USD 120 billion by 2050 from carbon markets alone.19 Initiatives like this and the great green wall could raise resources to fund nature protection activities.

The international financial system deploys annually about USD 100 billion in addition to some USD 30 billion deployed by the international development association (IDA).20 These resources are grossly inadequate to deal with the triple challenges of fighting poverty, building a sustainable planet, and increasing prosperity for all. The IEG report has called for a tripling of the resources made available to the MDBs to about USD 390 billion.21 It does not suffice to capitalize the MDBs; they also need to reform to become bolder and better, working more together as a system and, where possible, pulling resources for greater scale and impact. These include using their guarantees more effectively to provide credit enhancements to attract the private sector. Public resources would be fundamental to close funding gaps on loss and damage, for example, and dedicated agencies like the Green Climate Fund will remain important funding agencies for Africa. However, to restore trust in the system, these institutions must be adequately funded. The Bridgetown Initiative and the Nairobi Declaration all propose new and innovative ways of using concessional financing. High debt to GDP levels is crowding out much needed investments in climate. Implementing debt for nature swaps could help countries access additional financing.

The IMF’s USD 40 billion Resilience and Sustainability Trust is another important source of financing which provides long-term concessional financing. The provision of additional on-lending of Special Drawing Rights could augment the fund to USD 100 billion. Developing countries are calling for additional liquidity in the form of a new issuance of “climate” SDRs to help provide the liquidity needed to address the biggest challenge of our time. Regional Development Banks should become active recipients of SDRs.

The private sector, institutional investors, equity investors, domestic and foreign, would provide the bulk of the financing needed for mitigation and adaptation projects with a satisfactory risk adjusted rate of return. Sixty-six percent of Africa’s climate finance needs are mitigation needs where there is more private sector appetite.22 African pension and sovereign wealth funds are increasingly investing in climate projects. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero is supporting the Senegal Just Energy Transition Plan. Increasingly philanthropy capital is supporting project preparation and development for example the Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet. The climate challenge ahead for Africa is immense, however, with the right policy environment, adequate financing and country programs that deliver green industrialization as a core part of the solution, success is possible. Africa can and must do more to support the global ambition to end climate change while delivering prosperity for its citizens.

Viewpoints

More from Foresight Africa 2024

In Chapter 1, our authors share policy options to address economic challenges facing Africa.

In Chapter 3, our authors focus on policies to support Africa’s entrepreneurs and small businesses.

In Chapter 4, our authors examine trends in regional economic integration and trade.

In Chapter 5, our authors consider policy options to unlock the potential of the digital economy.

In Chapter 6, our authors explore the ways Africa’s women and girls are increasing opportunity for all.

In Chapter 7, our authors delve into ways African leaders can regain the trust of their citizens.

-

Footnotes

- World Meteorological Organization. “State of the Global Climate 2022.” WMO-No. 1316. https://library.wmo.int/viewer/66214/download?file=Statement_2022.pdf&type=pdf&navigator=1.

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2021. “Regional fact sheet – Africa.” Working Group 1 –The Physical Science Basis contribution to Sixth Assessment Report. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/factsheets/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Regional_Fact_Sheet_Africa.pdf.

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). 2023. “State of the Climate in Africa 2022.” WMO-No. 1330. https://library.wmo.int/records/item/67761-state-of-the-climate-in-africa-2022.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAO Food Price Index. https://www.fao.org/worldfood-situation/FoodPricesIndex/en/.

- FAO, AUC, EXA and WFP. 2023. “Africa – Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2023: Statistics and trends.” https://www.fao.org/africa/news/detail-news/en/c/1672786/.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). “Africa Energy Outlook 2022.” World Energy Outlook Special Report. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/220b2862-33a6-47bd-81e9-00e586f4d384/AfricaEnergyOutlook2022.pdf.

- Zero Carbon Analytics. 2023. “Loss and damage funding in Africa will be back on the table at COP28.” https://zerocarbon-analytics.org/archives/justice/keeping-loss-and-damage-alive-in-africa.

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). 2023. “State of the Climate in Africa 2022.” WMO-No. 1330.

- Cuni-Sanchez, A., Sullivan, M.J.P., Platts, P.J. et al. High aboveground carbon stock of African tropical montane forests. Nature 596, 536–542 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03728-4.

- FAO. 2021. “Africa Open D.E.A.L.: Open Data for Environment, Agriculture and Land & Africa’s Great Green Wall.” https://www.fao.org/3/cb5896en/cb5896en.pdf.

- O’Callaghan, Brian, Julia Bird, and Em Murdock. 2021. “A Prosperous Green Recovery for South Africa.” Oxford University Recovery Project, SSEE and Vivid Economics in partnership with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

- O’Callaghan, Brian, Julia Bird, and Em Murdock. 2021. “Green Economic Growth for the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Oxford University Recovery Project, SSEE and Vivid Economics in partnership with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

- O’Callaghan, Brian, et. al. 2021. “Green Economic Recovery for the Arab Republic of Egypt: Could green investment accelerate the COVID-19 recovery while at the same time making progress on climate change?” Oxford University Recovery Project, SSEE and Vivid Economics in partnership with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

- Ibid.

- Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance. 2022. “Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development.” https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/IHLEG-Finance-for-Climate-Action-1.pdf.

- Guzman, Sandra, et. al. 2022. “The State of Climate Finance in Africa: Climate Finance Needs of African Countries.” Climate Policy Initiative. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Climate-Finance-Needs-of-African-Countries-1.pdf.

- Songwe, Vera. 2023. “Financing Our Survival.” Project Syndicate.

- OECD. 2023. “Revenue Statistics in Africa 2023.” https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/brochure-revenue-statistics-africa.pdf.

- Climate Champions. 2022. “Africa Carbon Markets Initiative launched to dramatically expand Africa’s participation in voluntary carbon market.” https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/africa-carbon-markets-initiative/.

- The Independent Experts Group. 2023. “Strengthening Multilateral Development Banks: The Triple Agenda.”

- Ibid.

- Kone, Tiangoue. UNDP. 2023. “For Africa to meet its climate goals, finance is essential.”