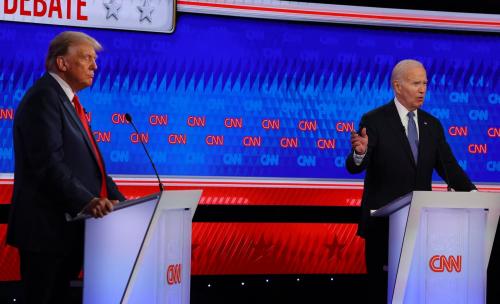

Last week, President Joe Biden and former President Trump met in Atlanta for a presidential debate. After the event, most observers focused heavily on Biden’s seemingly poor performance, while paying Trump’s many untruths and exaggerations far less attention. And now some Biden supporters are hoping he’ll quit the race and allow another candidate to replace him. To talk about those issues and to answer the big question, do presidential debates matter?, Governance Studies Senior Fellow Elaine Kamarck, founding director of the Center for Effective Public Management, joins The Current. She’s author of numerous works including “Primary Politics: Everything You Need to Know about How America Nominates Its Presidential Candidates,” now updated in its fourth edition for the 2024 presidential contest.

Transcript

[music]

DEWS: You’re listening to The Current, part of the Brookings Podcast Network, found online at Brookings dot edu slash podcasts. I’m Fred Dews.

Last week, President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump met in Atlanta for a presidential debate. After the event, most observers focused heavily on Biden’s seemingly poor performance while paying Trump’s many untruths and exaggerations far less attention. And now, some Biden supporters are hoping he’ll quit the race and allow another candidate to replace him.

To talk about those issues and to answer the big question, do presidential debates matter? I’m joined by Elaine Kamarck, founding director of the Center for Effective Public Management and a senior fellow in Governance Studies here at Brookings. She’s author of numerous works, including Primary Politics Everything You Need to Know About How America Nominates Its Presidential Candidates, now updated in its fourth edition for the 2024 presidential contest.

And let me add that leading up to the U.S. elections in November, Brookings aims to bring public attention to consequential policy issues confronting voters and policymakers. You can find explainers, policy briefs, other podcasts, and more. Plus, sign up for the biweekly email by going to Brookings dot edu slash election 24.

Elaine, welcome back to The Current.

KAMARCK: Thanks, Fred.

DEWS: I’d like to have this discussion in two parts. First, on the debate’s outcome and its salience, and then on these questions about President Biden. So first, can you put President Biden’s debate performance in some historical perspective? I’ve seen people talk about President Reagan’s poor showing against Mondale in their first debate in 84, and Barack Obama was thought to have lost to Mitt Romney in their first in 2012.

[1:48]

KAMARCK: Well, it is true that incumbent presidents in their first debate when they’re running for reelection, have a kind of a bad history. Okay? Reagan’s first debate against Mondale was memorable because he seemed to really lose it. And he was he was old then, not as old as Biden or Trump, but he was pretty old then. And he was wandering down the California highway, you know, seemingly in a kind of a confused daze. And, if you you can go on YouTube history and you can actually find the clip of that debate thing, and you’ll see Walter Mondale looking at him like, what are you talking about? Right? So, that was a pretty bad first debate.

On the other hand, in the second debate, he came back with one of the great lines of all time, which is, I refuse to take advantage of my opponent’s relative youth and inexperience. And they cracked up, cracked up the audience—they had an audience then—cracked up the audience and was repeated often and seemed to have neutralized feelings that maybe Reagan was not up to the job, that he was old.

And of course, we did realize several years after that that he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. And of course, that’s how he ended his life. So, that’s that is the case.

Obama had a pretty lackluster debate in his his first debate for his reelection.

So, it happens. And it has happened before. And, you know, it’s not surprising; people have various explanations for it. Incumbent presidents are sort of reluctant to have to, you know, debate when they’re they’re sitting presidents and they’ve got a lot of important things to do. They get out of practice, okay, when they’re president, I mean.

So, there’s a there’s a lot of explanations for that. But a bad first debate is not unusual for an incumbent president.

DEWS: Well, let’s look at then Donald Trump’s performance. Close observers of the debate said that Donald Trump lied throughout it. But the post-debate conversation was mostly about Biden’s poor performance. That seems like a double standard.

[3:55]

KAMARCK: It is a double standard, absolutely a double standard. But part of it is that Donald Trump’s lying is well known. It’s been it’s been followed ever since the first day of his presidency. He lied throughout his presidency. He makes up stuff all the time. And so, I think that for the press covering this, and I don’t mean to excuse them, but for the press covering this, this was old news that Donald Trump just made up stuff.

For Biden, what happened was there was a big question, which is was he too old for this office? And this was something that people were wondering about. And it was also something that the Republicans have been flogging since day one. They’ve really come down hard on that. And the reason I think this first debate made such news is that it seemed to play into the Republican narrative, it seemed to confirm the Republican narrative, and a lot of people were not sure that the Republican narrative was right. And now some people are saying, well, maybe it was so. So, that’s the difference between, I think, the way the two were covered.

DEWS: I assume you saw the aftermath of the debate. Biden was on the stage talking to people, and then the next day he was at a rally, I think it was in Raleigh, North Carolina, and he was a completely different person than he was during his time on the Atlanta stage.

[5:16]

KAMARCK: Well, he had a bad night. I mean, you know, it happens to all of us. And unfortunately, he had a bad night, you know, at the beginning of his of his reelect campaign. Look, this has been going on for some time now. Every once in a while, people will say, oh, they were with Biden, and he seemed sleepy. Or he seemed to get confused about something. And then he comes out and he does the State of the Union where he was fantastic and clearly, you know, firing on all fours.

So, it’s it’s it’s a little bit of up and down as it is with everybody. But when the entire world is waiting with bated breath for you to screw up, right, these screw ups are examined. And the good days, the good times are not examined. You’re not given much credit for it because you’re expected to always be on.

DEWS: It begs the question that I posed in the intro: do debates really matter? And in the context of the fact that both incumbent President Reagan in ‘84 and incumbent President Obama in 2012 went on to win reelection, do these presidential debates really matter?

[6:21]

KAMARCK: Oh, they they sort of matter, and the aftermath matters. And what matters about them is how they shape the narrative of the rest of the election. This debate performance of Biden’s was of concern because of the preexisting narrative that he was too old and no longer fit to, you know, to do the duties. And to the extent that he cannot overcome that in the next few months, that could be very dangerous.

To the extent that this never happens again, that it is a one off, that he had a cold, that he had a bad night, that the format was all wrong for him, I think he can probably get over it, but we don’t know the answer to that yet.

DEWS: And there’s another debate in this two-debate series planned to air on ABC on September 10th between the Republican and Democratic nominee. So, this is after the two conventions. Assuming both of these men are the nominees, what contribution do you see that encounter making to the electorate?

[7:23]

KAMARCK: Well, believe me, if that second debate happens—and, you know, if I were Donald Trump, I’m not sure I would take place in that second debate, because after all, you got everything you could possibly wish for out of the first one—if that second debate happens, people will be watching Joe Biden even more carefully than they were in this debate. And they’re going to look at his demeanor. They’re going to look at his clarity. They will look at everything, his walk onto the stage, you know, the whole business, I mean, so it’ll be even bigger than this debate.

DEWS: Let me ask you, Elaine, about the structure of these debates. This one was carried on CNN. The next one is going to be, if there is a next one, carried on ABC. Now, debates between or among leading presidential candidates from ‘76 to ‘84 were sponsored by the League of Women Voters. And from 1988 to 2020 they were sponsored by the Commission on Presidential Debates. This year, both campaigns declined to participate in the commission sponsored debates. What’s your view on what appears to be the exit of a third-party sponsor for presidential debates?

[8:30]

KAMARCK: I’m not sure it makes much difference. Okay? Because what is what is not generally known is that the format and everything that the the third party sponsor came up with was the result of an extensive negotiation between the two campaigns anyway. So, you always got as an end product you always got a negotiated debate. At this time, they just cut out the middleman and they did the negotiations themselves. So, I’m not sure that the absence of the sponsorship has much of an impact.

DEWS: Before we switch gears, I want to let listeners know that they can go find a piece that you coauthored with Bill Galston. It’s on our website, published last week. “Will Biden’s debate performance turn out to be fatal or just a bad night?” So, people should go read that.

Elaine, I’m going to look ahead and pose some of the questions that I’ve been hearing, and I know other people have been asking. The first one is that some Biden supporters are asking, why didn’t he step back before the campaign and let a new generation of Democrats vie for the nomination? Do you have any view on that?

KAMARCK: You know, I think that he was he made this decision right after the midterm elections in 2022. Democrats did really much better than expectations in those elections. I think he was feeling good and feeling confident in his role and that he figured, well, I feel good, I might as well do it again. And there was no obvious person to take over, and there was a fear that somebody else might not be able to beat Trump, whereas Biden had already done it once before. So, I think all of those things played into the calculations when he made them.

DEWS: I want to play Devil’s Advocate, too. I know people are asking this question or thinking these thoughts. If people wanted to see Biden replaced at the top of the Democratic ticket, how would that even be achieved, considering that all the primaries are over? And I believe Biden won at least 99% of the delegates and nearly every contest by a very large margin.

[10:41]

KAMARCK: It really couldn’t happen. I mean, if if he couldn’t be replaced, there’s no way to replace him. The only way that would happen is if he voluntarily took himself out of the of the race. He has the delegates, etcetera.

Now, the thing to remember is that the convention is what decides the nominee, not the primaries. The primaries elect delegates to the convention, but the legal authority for choosing the nominee of the Democratic Party, or for for that matter, the Republican Party, is not the primaries, it is the delegates voting in convention. When that happens, you have a formal nominee. You’re on every ballot in the country. You get federal election campaign money, I mean, etcetera, etcetera.

DEWS: And so, has there ever been a time when the presumptive nominee went into convention with the delegates in hand and something happened, and that person did not get the nomination? There was a convention that produced an unexpected outcome? I feel like this is something that may have happened in the 19th century.

[11:45]

KAMARCK: Yeah. Well, prior prior to 1972, this happened a lot. Okay? Prior to 1972, the the primaries really didn’t matter. What mattered was who the delegates were and who they voted for. So, prior to 1972, you had a lot of conventions where the result was a surprise, because in fact, people didn’t start making decisions until they got to the convention city.

And maybe one of the most recent examples to think about is in 1968, Lyndon Johnson decided not to run in March of that year, and that left the party without a presumptive nominee. Now, a lot of delegates had already been chosen, and they were, of course, Johnson delegates, and they tended to go to Hubert Humphrey.

And then as the season wore on, Robert F. Kennedy got into the race. McCarthy, Senator Gene McCarthy got into the race, had a lot of some antiwar people—it was this was all about the Vietnam War—got into the race. They picked up some delegates, too, but they could never pick up enough delegates to overturn the lead that Humphrey had. And much of that were Johnson people who whose allegiances switched Humphrey. So, that’s that’s a sort of the closest experience we’ve had in time.

DEWS: So, the Democratic National Convention is in August. Could you imagine for our listeners what it could be like at that convention if between now and then Joe Biden were to say, you know what, I am going to step down. What would that convention be like?

[13:28]

KAMARCK: Well, people would put their names in the pot to become the nominee of the party. They would campaign in a short period of time for the allegiances of approximately 4,000 people. How they would do that varies. I mean, there’d be a lot of phone calls. There would be a lot of delegation meetings. People would speak before delegations. I’m sure there’d be some debates, etcetera.

But it would be a very truncated campaign geared towards those 4,000, approximately 4,000 people.

DEWS: Elaine, I want to leave off with a question about a current event that’s come up. But before we go there, I do also want to let listeners know that you have a very thorough and excellent explainer on our website that’s going to answer a lot of questions that people have: “What happens if a presidential candidate cannot take office due to death or incapacitation before January 2025?” And it goes through various scenarios about when a candidate or when a nominee would be incapacitated or die during the cycle. I’ll let listeners find that on our website. Also put a link to that in the show notes.

I do want to ask you a question now about a case that was decided by the Supreme Court just today, just hours ago as we’re taping. And that’s the case on presidential immunity. The Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 saying that a president has presumptive immunity for clearly official conduct, immunity from criminal prosecution, that is. Do you have any thoughts on how this Supreme Court ruling and perhaps others factor into everyone’s thinking about what’s happening in the presidential contest?

[15:10]

KAMARCK: I’m not sure yet because it just came out, but I think it’s probably a blow to Trump in that he alleged that that presidential immunity was blanket. He said, I’ve got immunity for everything. And and most people thought that was pretty bad. I would suggest people look at Justice Sotomayor’s response to a part of her dissent on this.

On the other hand, it’s, it’s bad for Biden because, in fact, this kicks the can down the road, sends this back to the lower courts to decide what was official action and what was not official action. And that buys Trump more time. That’s what he’s tried to do with all of these court cases, the many court cases against him, he’s tried to get some more time. Obviously, he wants to, you know, keep any of these from happening until after the election.

DEWS: Okay. Well, Elaine, as always, thank you very much for spending some time with us on The Current today. It’s been very insightful, and I’m sure we’ll talk to you again during the presidential cycle.

KAMARCK: Great. Thanks, Fred. Bye bye now.

Commentary

PodcastAfter the first presidential debate, what’s next for Biden and Trump?

July 1, 2024