EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Over a period of several months in 2019, Pakistani and international media shone a spotlight on cases of bride trafficking that had been taking place around the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the $62 billion flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The practice involved cases of fraudulent marriage between Pakistani women and girls — many of them from marginalized backgrounds and Christian families — and Chinese men who had travelled to Pakistan. The victims were lured with payments to the family and promises of a good life in China, but reported abuse, difficult living conditions, forced pregnancy, or forced prostitution once they reached China.

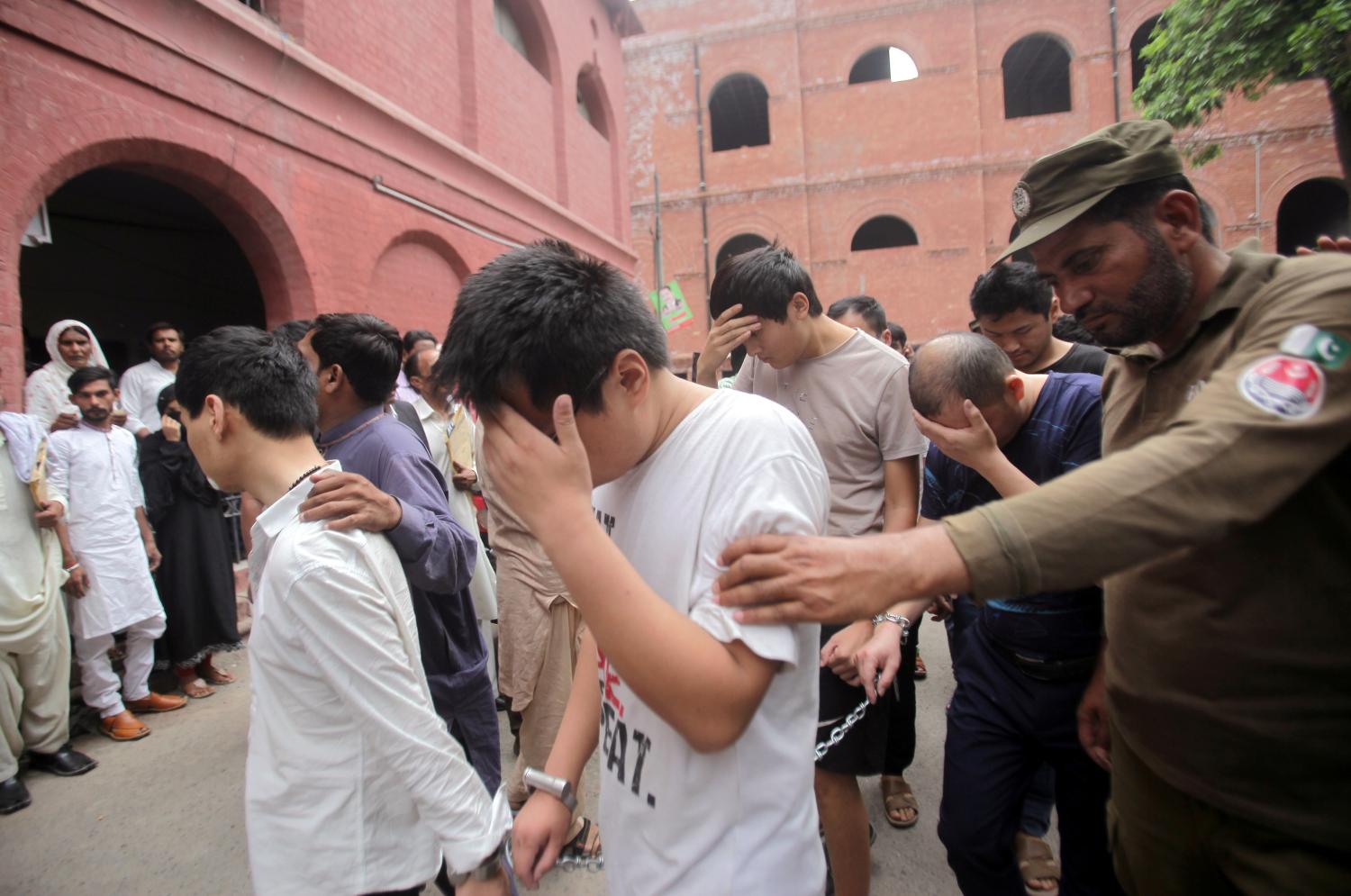

During this period of intense spotlight on the issue, Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency arrested and charged 52 Chinese traffickers. But by late 2019, more than half of the traffickers had been acquitted in a Pakistani court, the others were all given bail and flown out of Pakistan, investigators were pressured by Pakistani authorities to let the cases slide, and journalists were asked to curtail their reporting on the issue.

Such cases of Chinese bride trafficking are not confined to Pakistan: the practice has been documented in Laos, North Korea, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia. At the root of the issue is China’s demographic gender gap, driven by its previous one-child policy, male preference, and the practices of selective abortion and in some cases even female infanticide that followed it, estimated to have resulted in some 34 million more men than women in China.

What made the Pakistani case different from the other contexts where such trafficking took place was the initial government and media attention to the issue, and how it was brushed under the rug soon after. Explaining it are two offsetting imperatives: first, the deeply disturbing nature of the crime for Pakistani society, given Pakistan’s cultural emphasis on protecting women’s “honor” — which explained the attention to the issue. The second imperative — which ultimately won out, and led to attention to the issue being stamped out — was the need to protect Pakistan’s exceedingly close relationship, economic and otherwise, with China, given the lopsided power dynamic between the two countries. Regardless of that dynamic, Pakistan’s government owes it to its citizens to be more assertive with China on human rights abuses that affect them.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Ted Reinert edited this policy brief, and Rachel Slattery provided layout. Brookings is grateful to the U.S. Department of State and the Institute for War and Peace Reporting for funding this research.