Language is constantly evolving. Reflecting the fluidity of labels used within the Latino community, the following terms are used across the article, often interchangeably: Hispanic, Latine, Latino, and Latinx. By no means is this list exhaustive.

Over the last several years, two important economic trends in the United States have become intertwined. This first is the rise of the Latino community as an economic force, as the demographic rapidly expands across the country while still facing barriers to wealth-building and opportunity that other groups do not. The second is the exploding popularity of financial technology, or “fintech”—new products and services that promise to revolutionize banking, investments, and other areas, especially for historically excluded groups. Today, Latinos are embracing fintech at high rates compared to other groups, yet a stark absence of data and research is preventing policymakers and other stakeholders from understanding the technology’s impact on this critical segment of the population.

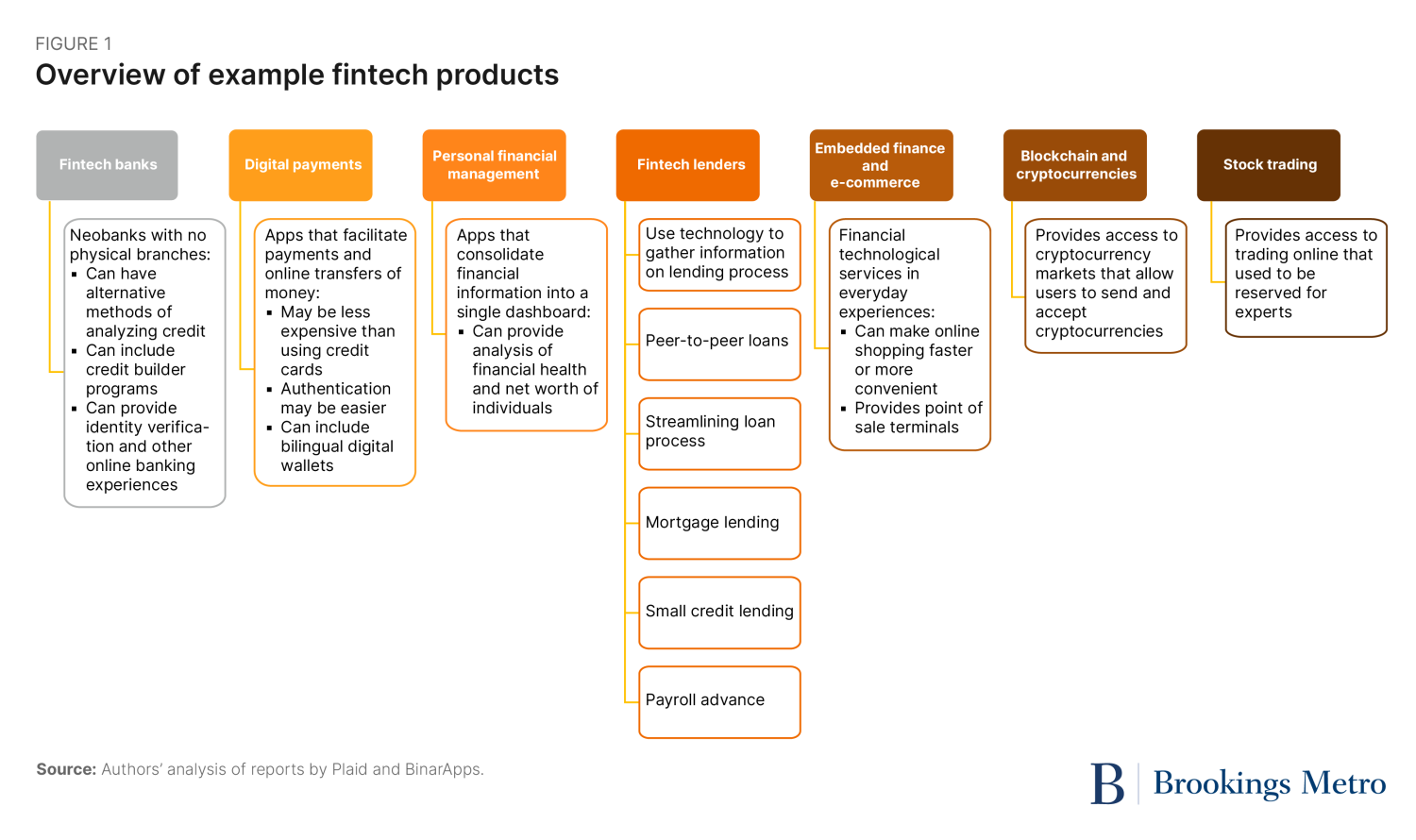

Fintech is a catch-all term encompassing a wide range of financial products and services that use technology and innovation powered by AI, big data, and blockchain technology (Figure 1). The fintech industry has grown exponentially over the last few years, not only in the development of new products, but also in its number of users. This rapid growth has prompted arguments that fintech can bolster financial inclusion, presumably by lowering barriers to entry, allowing fractional investment, creating automated investment platforms, digitizing banking, opening peer-to-peer lending and crowdfunding, and lowering costs, among other ways.

This narrative suggests these characteristics may be appealing to communities of color, including Latine families, who have been historically excluded from accessing basic financial products and services. While some fintech products are intended for mass audiences and have high Latino adoption rates, others are tailored specifically for the Latino market—ranging from bilingual digital wallets to neobanks, and providing an array of financial services, including to immigrants without Social Security numbers.

During this Hispanic Heritage Month, this report examines the potential and pitfalls of fintech for Latine communities, and presents a more nuanced view of how these technologies can help—or not help—overcome existing barriers to accessing safe and affordable financial services.

Importantly, Latinos in the U.S. are not a monolith, and understanding their needs and preferences requires detailed, disaggregated data. As such, the report also highlights the limited data that exists on Latinos’ fintech adoption rates and experiences, and why more is needed to connect Latinos’ broader wealth-building challenges and opportunities to their adoption of and perceptions toward emerging technologies, particularly in a post-pandemic world. The report delineates the importance for collecting more data to understand Latinos’ motivations for using fintech products and services, how they are using them, and whether or how they experience risks and benefits.

Latinos are adopting fintech at high rates, but we need to understand their motivations and how they are impacted

Some data on fintech adoption rates indicates that among racial groups, Hispanic people use the technology at the highest rate (92%) compared to white (74%), Asian American (79%), and Black (88%) consumers.

There are a host of reasons why Latinos may gravitate to fintech. Latinos skew younger, for example, and younger consumers are often more eager to adopt new technologies. Meanwhile, research shows Latine communities face a host of barriers to accessing financial services, which may cause them to seek out alternatives such as fintech. Latinos face language or experiential barriers (such as negative past experiences with financial services), economic barriers (high fees and rates), and structural barriers (racism, discrimination, difficulty building credit scores, and predatory financial services). Fintech proponents primarily focus on addressing experiential and economic barriers, such as lowering fees and offering Spanish-language apps. There is less of a focus on structural barriers, such as avoiding predatory behavior, addressing discrimination, or bridging identification issues for people that file taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) because they lack a Social Security number.

Nevertheless, a scan of media reports seems to suggest, at least anecdotally, that Latinos may be attracted to some fintech products because they seek more avenues for building wealth or accessing basic financial services—a result of feeling excluded from or lacking trust in traditional financial services.

Indeed, there are stark differences in banking status between white and Hispanic families at every income level. For example, 8.4% of Hispanic households are unbanked, compared to only 1.7% of white households with incomes between $30,000 and $50,000. Among the reasons unbanked households cited for not having a bank account, 21% of respondents indicated not having enough money to meet the minimum balance requirements, 13.2% cited distrust in banks, and 6% cited bank account fees.

While trust cannot be built instantaneously, it is a crucial element for impacting equity in the financial system over time. Some Latinos also anecdotally cite their family members’ negative experiences with traditional financial avenues and predatory loan products as reasons to turn to fintech. As an example, the 2008 financial crisis decimated Latino and Black wealth through risky subprime mortgage loans; Hispanic families lost 44% of their wealth between 2007 and 2010. Yet while there are anecdotal reports, no survey to date connects the Latine community’s broader experiences with wealth-building barriers and opportunities to their adoption and perceptions toward fintech, particularly in a post-pandemic world.

Latinos may also find fintech products appealing due to lower fees and fewer barriers to entry. For example, surveys indicate that Hispanics are more likely to cite fees as their biggest financial challenge (31%), compared to white (15%) and Black (20%) consumers. Likewise, small-dollar fintech loans, which allow access to credit for consumers with limited credit history, may appeal to Latines, since they experience barriers to building credit. Fintech payroll advance services, which provide early access to earned wages, also appeal to Hispanic consumers (at a rate of 32%) more than white (13%) and Black (13%) consumers.

Latinos also appear to embrace cryptocurrencies, possibly because they have fewer barriers to entry. While cryptocurrencies are available to mass audiences, some surveys indicate higher Latino adoption rates. One survey found Hispanics represent 24% of cryptocurrency owners (while just 16% of U.S. adults overall identify as Hispanic). Another found that when asked which is more accessible between crypto and traditional finances, nearly half of Black (46%) and Hispanic consumers (44%) said crypto, compared to 29% of white consumers. This same survey noted that more than half of Hispanic consumers (54%) thought crypto will play some role in their future financial decisionmaking, compared to 43% of Black and 33% of white consumers. Unfortunately, though proponents claim that crypto bolsters financial inclusion for communities of color, including Latines, research has shown these types of technologies may not actually meet these communities’ needs, and could present more risks than opportunities, including prevalent scams, fraud, and hacks.

While these surveys, reports, and news articles are illuminating, more data is needed to understand Latino adoption rates across a host of fintech products, their motivations for using them, and how they are impacted by them.

Fintech should not come with conditions undermining benefits for Latinos

Importantly, when discussing innovation and technology in general, the “potential” of technology is often discussed in positive terms. Yet there are many examples of technologies not living up to their positive potential, or harming industries, communities, and individuals. Thus, policymakers and private sector actors should ensure whatever “access” or other benefits fintech products and services provide do not come with conditions that undermine those benefits (i.e., predatory inclusion). Robust consumer protections should also be applied to fintech products and services.

When it comes to fintech, many companies tout their products as offering cheaper, faster, and more convenient services than traditional financial products and services, which increases customer satisfaction or fills a market gap. In some cases, fintech companies aim to tailor products and services to specific markets, including Latino markets (e.g., providing language access in apps), thereby addressing nuanced concerns or barriers these markets would otherwise encounter when using traditional financial services. These are all important areas for expanding access to financial services for Latino communities.

But there are common features of fintech that can undermine its potential benefits, including a lack of robust data security and privacy systems, a lack of transparency around costs (including hidden fees) and business models, avoidance of consumer protection laws, and encoded racial bias. Furthermore, there are risks associated with how big data is used; potential for fraud, scams, bugs, and hacks; lack of avenues for redress when things go wrong; and reproductions of predatory or discriminatory practices in a digital format.

For example, fintech products such as “buy now, pay later” (BNPL) platforms lack transparency around costs, have inconsistent consumer protections, and operate in a regulatory gray area. Many academics, consumer advocates, and some federal agencies recently raised alarms about the BNPL bubble. According to a recent report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Latine (24%), Black (26%), and female consumers (20%), as well as households with income between $20,000 and $50,000, were significantly more likely to borrow using BNPL products compared to white (14%), non-Latine (15%), and male consumers (14%), or households with income below $20,000. While BNPL platforms market purchases made through their platform as “interest free,” consumers can end up paying more than they originally plan. Some loans through these platforms can have high interest rates if consumers are not able to secure 0%. Moreover, BNPL can come with many fees that consumers might not initially be aware of, such as late payment fees, reschedule payment fees, or return fees. Some loans are also reported to credit bureaus, and since BNPL platforms do not conduct in-depth consumer credit checks, a consumer is more likely to miss payments, which could impact their credit score. According to a survey by LendingTree, 42% of consumers who took out a BNPL loan made a late payment on one of those loans.

Meanwhile, policymakers can learn many lessons about emerging technologies from the demise of the cryptocurrency hype cycle, including how demographic targeting, risks, and scams could harm Latino consumers. For instance, the collapse of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX initiated a ripple effect of crypto companies filing for bankruptcy and retail investors losing their life savings. These crashes impacted investors of color, and retail investors from lower-income backgrounds fared worse than those with higher incomes.

Notably, crypto companies targeted Latinos by marketing certain aspects of their products without disclosing the negatives. For instance, just as payday lenders set up shops in areas with certain demographics, bitcoin ATMs—which are notorious for charging exorbitant hidden fees, ranging from 7% to 20% per transaction—cropped up in Latino grocery stores. These ATMs also clustered in Salvadoran, Colombian, and Mexican neighborhoods in metro areas such as Miami, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Los Angeles. While this was taking place, crypto scammers targeted Latinos in Chicago and Houston as well as Spanish-speaking immigrants in Maryland. Even though many actors across sectors promoted cryptocurrencies, more due diligence on behalf of policymakers could have saved consumers from harm.

In that vein, researchers, policymakers, and private sector actors should pay close attention to nonbank online lending, including fintech small business and mortgage lending, since these lenders can impact Latinos’ wealth-building opportunities. While nonbank online lenders may be touted for increasing access to credit and loan products to historically excluded communities, they can also come with conditions that substantially undermine those benefits, including higher costs, fees, and interest rates.

For example, as access to capital remains an obstacle for Latino entrepreneurs, more nonbank online lending options are emerging. The Federal Reserve Banks’ 2022 Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS) noted that Black- and Hispanic-owned firms (33% and 29%, respectively) were more likely than white- and Asian-American-owned firms (23% and 20%, respectively) to apply for loans with nonbank online lenders. Although this may seem like a positive indication of Black and Hispanic entrepreneurs’ experiences with fintech, in reality, fintech lenders had the lowest net satisfaction rates among all applicant firms.

Moreover, while the 2023 SBCS did not break down responses according to race or ethnicity, it noted that applicants chose an online lender because of the expected speed with which a decision or funding would be made (55% cited this reason), their perceived chance of being funded (48%), or lack of collateral requirements (46%). Yet, those who applied to nonbank online lenders did report challenges with high interest rates (44% cited this challenge) and unfavorable repayment terms (34%). Considering that Latino-owned businesses employ more than 3 million people and represent the fastest-growing segment of U.S. businesses, there is a need for more research on fintech loan products and wealth-building as a whole to ensure Latinos have access to safe, affordable ways to start and grow their businesses.

Fintech mortgage lending is another area where increased “access” to a product or services may not always be a good thing. Fintech mortgage lending is characterized by its all-online application process (compared to a traditional mortgage lending process, which takes place in person), and its inclusion of proprietary machine learning algorithms and alternative data in making underwriting decisions. While one study found that disparities in loan approval rates are lower with fintech lenders relative to traditional lenders, it also pointed out that nonwhite applicants are more likely to receive subprime terms in their approvals.

Similarly, another spatial study examining regional differences in fintech and traditional lending at the neighborhood level across immigrant gateway metro areas found that subprime lending overall is higher in tracts with more Black and Latino residents relative to tracts with more white residents, which is consistent with other studies. They also found that immigrant gateways, including Latino immigrant communities, had higher rates of subprime lending from both fintech and traditional lenders than non-immigrant neighborhoods.

Due to Latinos’ potential to drive homeownership growth and their history of being targeted for subprime loans and experiencing foreclosures, it is important to further explore nonbank online lenders’ impact. Future research should examine Latinos’ motivations for turning to nonbank online lenders, their approval rates, whether they received regular or subprime loans, and how fintech impacted their home purchase (for better or worse).

More data and research are needed to understand Latino fintech adoption

There are significant knowledge gaps when it comes to why Latinos are drawn to fintech products and services. These gaps affect public policy decisions, particularly as fintech products and services emerge as alternatives to traditional financial services for communities that cannot access them.

A better understanding of how Latines use fintech products more broadly would help policymakers at various levels of government develop policies, legislation, and regulations that promote overall financial well-being for Latine families and prevent predatory behavior toward communities of color. It would also aid private stakeholders in designing products and services that mitigate risks and barriers associated with new technologies and other more traditional financial products.

In particular, more data is needed to understand how and why Latines use fintech products, and the risks they may face when using them. While some surveys, such as Fintech Effect for fintech usage or NORC for cryptocurrency trends, have started collecting data on fintech use by demographic groups, specific data on Latinx communities remains sparse. We find the following gaps:

Data on how Latines use fintech products: As noted earlier, no survey to date has connected the Latine community’s broader experiences with wealth-building barriers and opportunities to their adoption and perceptions toward fintech, particularly in a post-pandemic world. More survey data should examine Latine households and supplement existing national datasets on financial wealth in the U.S. by providing detailed data on attitudes and perceptions of household finances, as well as how fintech products impact Latines more broadly. Moreover, given the Latine community’s diversity, data should be disaggregated between different Latine groups to understand how personal characteristics, acculturation levels, and different backgrounds may deepen barriers or enhance opportunities.

Data on why Latines use fintech products: While anecdotal evidence indicates Latinos view fintech as a potential solution to the financial barriers they face, there is little data suggesting they trust fintech more than other financial institutions. In order to determine whether Latinos’ perception of trust or distrust in traditional financial institutions or whether barriers they face correlate with fintech adoption, a more comprehensive study is needed. Are there barriers to getting the loans they need to build wealth or address an emergency? Do these encounters lead them to seek out alternative products and services, including fintech? If they distrust the banking sector, what specifically do they distrust and why? More qualitative data on the context behind their fintech use and a holistic understanding behind participant responses and motivations are needed to truly understand the role of trust and opportunity behind fintech.

Data on potential risks Latines face when using fintech products: Given fintech’s portrayal as a driver of financial inclusion, more data is needed about potential risks these products have on Latines’ financial well-being and inclusion, including an analysis of the impact of hidden costs and unexpected fees.

Studying Latino use of fintech is critical for fostering their financial well-being

Fintech products and services are thought to be transforming financial services and thus are considered an important component, if not driver, of the future of finance. But by failing to critically engage with Latine communities and ignoring barriers or opportunities associated with their wealth-building efforts, we limit not only Latines’ economic mobility, but also the nation’s economic future.

More data on how Latines engage with and are served by fintech will help both policymakers and private developers design and regulate policies, products, and services driving financial inclusion, and foster financial well-being for a growing and important segment of the U.S. population. More data may also bolster the case for stronger banking systems that can enable historically excluded communities to access financial services and products and build wealth in a safe and sustainable manner.