One of the keys to sustained and successful democracy is access to credible information about the state of the country and the people competing for its leadership. This access is under threat due to myriad factors: political polarization; the decline of local newspapers; the paucity of opportunities for post-secondary education in our country’s poorest places; the resulting gaps in both education and opportunity levels in those populations and places; and the crisis of despair that is reducing health and longevity in many of those same places. That context provides a perfect breeding ground for the spread of dangerous misinformation that is jeopardizing our democracy. It is imperative that we pay attention to this trend, how it affects those most vulnerable to it, and the role in could play in the upcoming presidential election.

Why is misinformation a problem?

The trends in the decline in local newspapers—which are critical to accountable local government, civil society, and credible information about current events—are stark. Only 1,213 daily newspapers are still operating in the country. Yet there are 1,265 fake local news websites—4% more than the remaining newspapers. The fake news sites are often funded by “dark money” from external sources seeking to influence electoral outcomes. This has corrosive implications for the electoral process, particularly in those places that lack adequate local news sources.

Misinformation is also a strategy that other countries—Russia in particular—are using to influence the outcome of the 2024 election. Russian state media accounts, for example, are actively employing Tik Tok to reach U.S. voters. This fits into a broader picture of what FBI Director Christopher Wray has called “a rogues’ gallery” of foreign organizations calling for violence against Americans. Yet he also suggested that more pressing danger is coming from individuals and small groups in the U.S., resulting in joint threats to our public safety and national security at the same time.

In the immediate term, election integrity is under threat and a paramount concern; in the long run at stake is our civil society, our health and longevity—due to health misinformation and deaths of despair; our education system, which is being undermined by the decreasing trust in science; and the productive potential of our young, as those who have poor mental health particularly vulnerable to misinformation.

The role of despair in the misinformation equation

We have increasing numbers of citizens in despair, with a significant increase among our young beginning in 2011. New research by neurologists finds that people in despair are particularly vulnerable to misinformation, conspiracy theories, and the radicalization that often results. Skepticism about the value of education, meanwhile, which in part results from despair, is a key factor in the erosion of belief in science. These factors result in a weak base upon which to challenge fake news and rumors, and they all too quickly become “the truth.”

Despair is, most simply put, lack of hope. Despair describes the plight of the many that are ambivalent about whether they live or die. The latter impacts risk taking, as in behaviors that jeopardize health and longevity. Entire communities can experience this helplessness. “Deaths of despair” is a term coined by Anne Case and Angus Deaton that describes the premature deaths due to drug overdoses, alcohol poisonings, and suicide that have taken over a million lives in the past decade and precipitated a consistent decline in our national average life expectancy since 2015.

Not coincidentally, these deaths are disproportionately concentrated in the very same places in the country where misinformation is most rampant. Not only do many of those places display the economic, civic, and opportunity deficits noted above, but they also have a high concentration of prime-age labor force drop out, low geographic mobility, poor health indicators, and high rates of despair and opioid addiction. The same places have also experienced the largest declines in local newspaper access and in other features of community life that typically accompany the disappearance of local jobs.

What can we do about it?

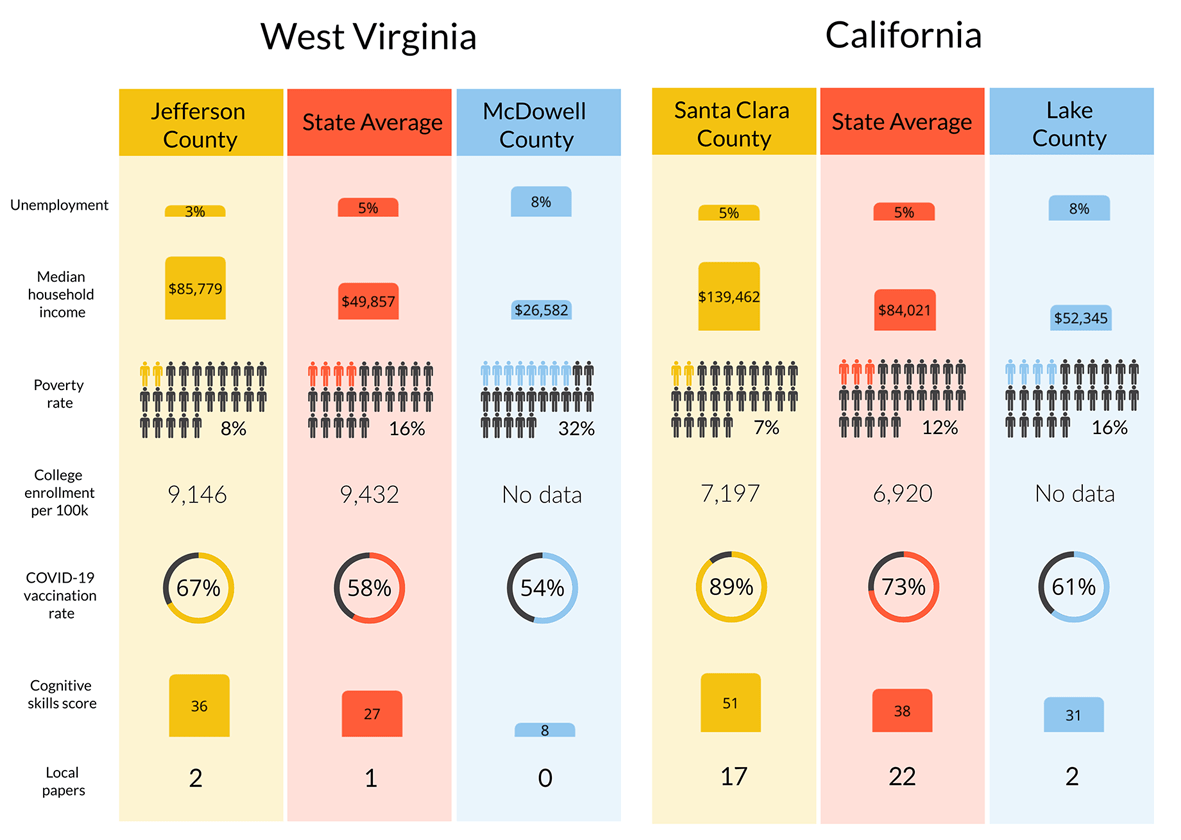

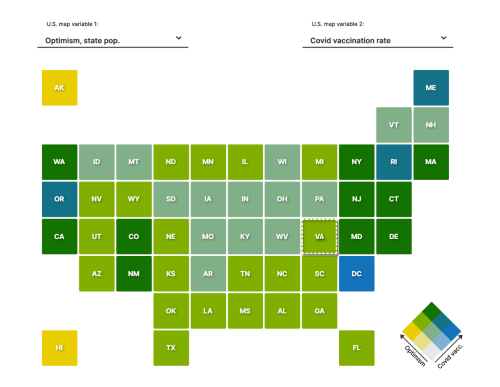

Finding viable solutions to the problem is more difficult than diagnosing it. As a first step, we have built an interactive which highlights the places and populations that are most vulnerable to despair and information. The interactive presents county level information on despair, access to credible local news, cognitive skill levels for high school graduates, COVID-19 vaccination rates, and access to higher education opportunities. As is clear from Figure 1, counties in the same states can have very different levels of vulnerability to misinformation depending on their access to the above public goods and services, which is why having information on them is critical. It is our hope that academics and local and state level policymakers can use this tool to identify vulnerable places and populations and develop policies to aid them.

Figure 1

Figure by Isabel Shaheen O’Malley

Supply-side solutions must focus on preventing the spread of misinformation through better regulation, directing law enforcement efforts on the illegal actors who fund questionable content, and changing how we finance and produce local news, among other strategies. But they alone will not work if there is demand among increasingly desperate populations.

Efforts to curb demand for misinformation include reforming our education system, which is failing to deliver on the skills kids need for the labor markets of tomorrow if they are not lucky enough to afford the increasing costs of a college education; addressing the eroding trust in science and health information; increasing access to mental affordable mental health care and reducing the stigma against mental illness; and investing in the revival of declining communities.

Further, these interventions must incorporate communities in the proposed solutions and support community-level wellbeing through better health care, including mental health. Despair at the individual level is often linked to community-wide despair, in contrast to high levels of individual happiness having positive spillover effects on others in the same neighborhood or network.

One model with potential for replication in a wider range of places is reviving local newspapers based on a new role for philanthropy, as many papers are shuttered because of declining revenue due to competition from online outlets or social media. Such efforts have recently supported the creation of new local newspapers, such as the Baltimore Banner. This would also address the demand side of the problem, as local news tends to foster community spirit, better local government, and local economies, making misinformation less credible or appealing.

There are also models for how to reform education so that it can deliver skills students need in the work force. Germany and the U.K. provide some interesting examples on this front, with a strong focus on linking education to career paths in specific industries.

Another important piece of this puzzle is addressing our increasing levels of mental illness, especially now among the young. This will surely take time, and there is a paucity of available mental health care in the places that need it most. It will entail creating new models of delivery, as it is evident that the traditional individual doctor-patient model is unable to keep up with the increasing demand for services. There are now many examples of care delivery which involve community members in providing peer support, identifying the vulnerable, and identifying resources that can support those in need. These efforts also play the critical role of reducing the stigma that is often attached to seeking help for mental illness.

Finally, we need to teach individuals—particularly the young—and communities how to identify misinformation. In Finland, for example, there are programs integrated in school curriculum to do exactly that.

Conclusion

To truly address our misinformation crisis, which poses immediate challenges to the 2024 election as well as longer-term ones to our society’s health, longevity, democracy, and civil society, both the demand and supply sides of the problem will need to be addressed. While the latter focuses on solutions such as better regulation of social media and fake news, the former requires fundamental changes to the systems that deliver critical social services and public information.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

Commentary

Our twin crises of despair and misinformation

How they threaten the 2024 election – and our democracy

July 22, 2024