The 1963 March on Washington, formally entitled, “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” brought critical national attention to the political and social conditions of Black Americans, as commemorated in the movie, “Rustin,” a film about Bayard Rustin’s notable contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. The March on Washington is the time and place Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his powerful “I Have a Dream” speech, and was led by “The Big Six” civil rights groups, which showcased the Black men leading the organizations. Yet, in the background were Black women, who had less prominent public positions but just as important roles leading organizational and parallel efforts fighting for racial equality and the advancement of civil rights for Black people. Behind the scenes in 1963, Black women were bringing national attention to racism and injustices but were rarely given prominent organizational roles or speaking time on the mic during public programs, and their contributions are seldom highlighted. The lack of recognition, however, does not diminish their advocacy, organizing skills, and their ability to motivate others.

The work of Black women was integral to bringing people to Washington, D.C. in 1963, specifically Anna Arnold Hedgeman of the National Council of Churches and Dorothy Height, President of the National Council of Negro Women. These two Black women, as well as others, like Mary McLeod Bethune, had rightfully gained their place among other prominent civil rights leaders.

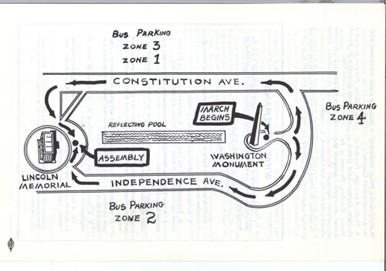

Black women have always viewed political and civic engagement as a means to achieve full equality and improve the social and political conditions of Black Americans in the U.S. and have long engaged in political movements through their individual and collective activism. But they are not always showcased, their work often goes underappreciated, and their interests are frequently diminished, ignored, or separated from the interests of Black men. For instance, men and women held separate marches in 1963. Women led other women down Independence Avenue toward the Lincoln Memorial while men led other men down Constitution Avenue.

Map of the route from the March on Washington program. Miscellaneous Accessions, 2003-36

The division of men and women was also evident in who had key speaking roles at The March on Washington. Initially, Black men leading multiple civil rights organizations opposed giving a single Black woman a prominent speaking role and instead they were asked to serve in supporting roles: emcee the program (Ruby Dee emceed the program with her husband, Ossie Davis) or speak or sing when the men were not on the mic. For instance, Odetta Holmes sang spirituals and a medley of freedom songs. Mahalia Jackson, known as the Queen of Gospel, performed two hymns Prior to The March, Black men compromised by adding a “Tribute to Negro Women Fighters for Freedom” to the program. Myrlie Evers was chosen to deliver the “Tribute to Negro Women Fighters for Freedom.” The negotiation for giving a Black woman a prominent speaking role on the program was led by Hedgeman and Height, as well as other Black women, such as Corinne Smith and Geri Stark, fundraisers with the Negro American Labor Council, who worked to add women to the official program and have Black women given equal time on the mic. Hedgeman and Height argued that women should be included as official and substantive speakers.

In addition to the Tribute to Negro Women, Gloria Richardson, co-founder of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee, was invited to give a two-minute speech, but an event marshal took away the microphone after she spoke one word: “Hello.” Lena Horne was introduced and shouted a single word into the microphone: “Freedom!”

Rosa Parks spoke to the crowd, saying, “Hello friends of freedom. It’s a wonderful day and let us be thankful we have reached this point, and we go farther from now to greater things. Thank you.”

Josephine Baker, a civil rights activist and renowned performer, had the most time on the microphone for a Black woman. She shared her love of seeing so many people on the Mall, that “without unity there cannot be any victory,” also adding, “I just came because it was my duty and I’m going to say again you are on the eve of complete victory. Continue on. You can’t go wrong. The world is behind you.”

When it was time for Myrlie Evers to speak, due to the overwhelming size of the crowd and traffic congestion, she was not able to make it to the stage in time; in her place, Daisy Bates was asked to fill in. Daisy Gatson Bates, born and raised in Arkansas, started the Arkansas Weekly with her husband. The Arkansas Weekly was the only African American newspaper solely dedicated to the Civil Rights Movement. As a civil rights activist and President of the Arkansas chapter of the NAACP, Bates was integral to the formation and implementation of the strategy to challenge segregated schools. Bates organized the Little Rock Nine.

In her 1963 speech, Bates named and acknowledged other Black women who had contributed to the fight for freedom, and said:

…we will join hands with you as women of this country. Rosa Gragg [president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs], Vice President; Dorothy Height, the National Council of Negro Women; and the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority; the Methodist Church Women, all the women pledge that we will join hands with you. We will kneel-in; we will sit-in until we can eat in any corner in the United States. We will walk until we are free, until we can walk to any school and take our children to any school in the United States. And we will sit-in and we will kneel-in and we will lie-in if necessary until every Negro in America can vote. This we pledge to the women of America.

In an after-action meeting about The March, prominent Black women in the Civil Rights Movement focused on how to move forward and address the “missingness” of Black women. This was especially true, because after The March, Richardson shared that she felt that Black women were treated as second-class citizens during the event. Pauli Murray, a civil rights attorney, argued that the substantive exclusion of women from The March on Washington program meant that future activism needed to focus on gender and racial equality to highlight Black women and their contributions to the fight for freedom.

In 2023, we celebrated the 60th Anniversary of The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the 50th anniversary of hip hop, and Black women have more than earned their right to be on the mic. Black women are creators and activists, politicians and leaders, and their contributions should be acknowledged, uplifted, and celebrated regularly so their stories are not lost. Thankfully, in 2023, Black women were on the mic for the 60th anniversary of The March, which included Bernice and Yolanda King, the daughter and granddaughter of Martin Luther King, Jr., U.S. Representative Nikema Williams (D-GA), and other Black women holding powerful positions in government, such as Vice President Kamala Harris. Additionally, 28 Black women are U.S. Representatives and eight Black women are currently mayors of some of the most populous cities in the nation. Moreover, Black women serve as a critical voting bloc for the Democratic Party and will continue to be the torchbearers, advocates, and leaders for the next generation of civil rights activism.

Commentary

Black women on the mic during the 1963 March on Washington

June 26, 2024