The emerging solidarity economy:

Introduction

Residents in South Los Angeles’ Crenshaw neighborhood are in the midst of a battle against developers—seeking to block the sale of the 41-acre Baldwin Hills-Crenshaw Plaza Mall to institutional investors that would turn the property into luxury housing and threaten to displace the city’s last majority-Black community. It’s a story that could occur in any hot-market city in the nation, except for one key detail: the Crenshaw community is equipped with over $28 million in donations and another $30 million in pledged impact financing to back up their efforts. Black organizers raised this money to purchase and develop the prime commercial real estate into mixed-income housing, worker-owned cooperatives, and new green space for community benefit. They are grounding their efforts in a larger “solidarity economy” movement designed not only to shape the forces of development in Crenshaw, but to fundamentally reshape how the country thinks about development and community control. As one organizer told us, “We want to create a roadmap as an antidote to the bad Kool-Aid these developers have been selling.” If they are successful, it will be an unprecedented win in the fight for community control of commercial real estate.

While community ownership efforts such as these have garnered new attention lately, the solidarity economy is generations in the making. Property ownership in the United States has always been rooted in racial exclusion and exploitation, from the theft of indigenous lands, to slavery, racial housing covenants, predatory lending, the use of eminent domain for highway construction, and the systemic devaluation of Black residential assets.[1] This enduring link between ownership and structural racism undergirds many economic disparities faced by individuals and communities of color in the U.S., including the racial wealth gap, disproportionate rates of asset poverty,[2] intergenerational poverty, access to credit, capital, and entrepreneurship opportunities, and economic mobility.[3]

Yet, for as long as long these inequities in wealth and ownership have tainted America’s economic fabric, Black families and other economically excluded populations have piloted collective ownership models—including communal farming plots, Black commons, Freedom Farms, Black credit unions, mutual aid networks, and community land trusts.[4] These models are not only about collective ownership of property, but also about fostering community self-reliance, community-led development, and redistributing power from exploitative systems. Today, as we seek to recover from the pandemic-induced economic crisis, interest in these models has surged, yet widespread adoption remains elusive.

The purpose of this brief is to help readers understand community ownership as a movement, policy choice, and mechanism for achieving resident-led community resilience and revitalization. We define and summarize various community ownership models, trace their evolution, present the evidence base on their benefits, and discuss the structural barriers that prevent these models from being adopted in more places. We conclude with recommendations for how local, state, and federal leaders can support community ownership as an emergent strategy for equitable development.

What is community ownership?

The concept of community ownership[5] itself is simple: A defined “community” purchases property, determines the ownership model that fits it needs, and shares in the risks and benefits of ownership and stewardship as a community.[6]

Yet, it is difficult to find a standard definition of community ownership. When Shelterforce put out a call for readers to define “community control of land” in 2018, the most common responses included principles such as: “the desire to remove land from speculative, profit-driven cycles;” “permanent affordability;” and “creating healthier places to live through collective decisionmaking.”[7] Yet the nuances of community ownership are in the details.

Four questions are useful for understanding what “community ownership” means in practice:

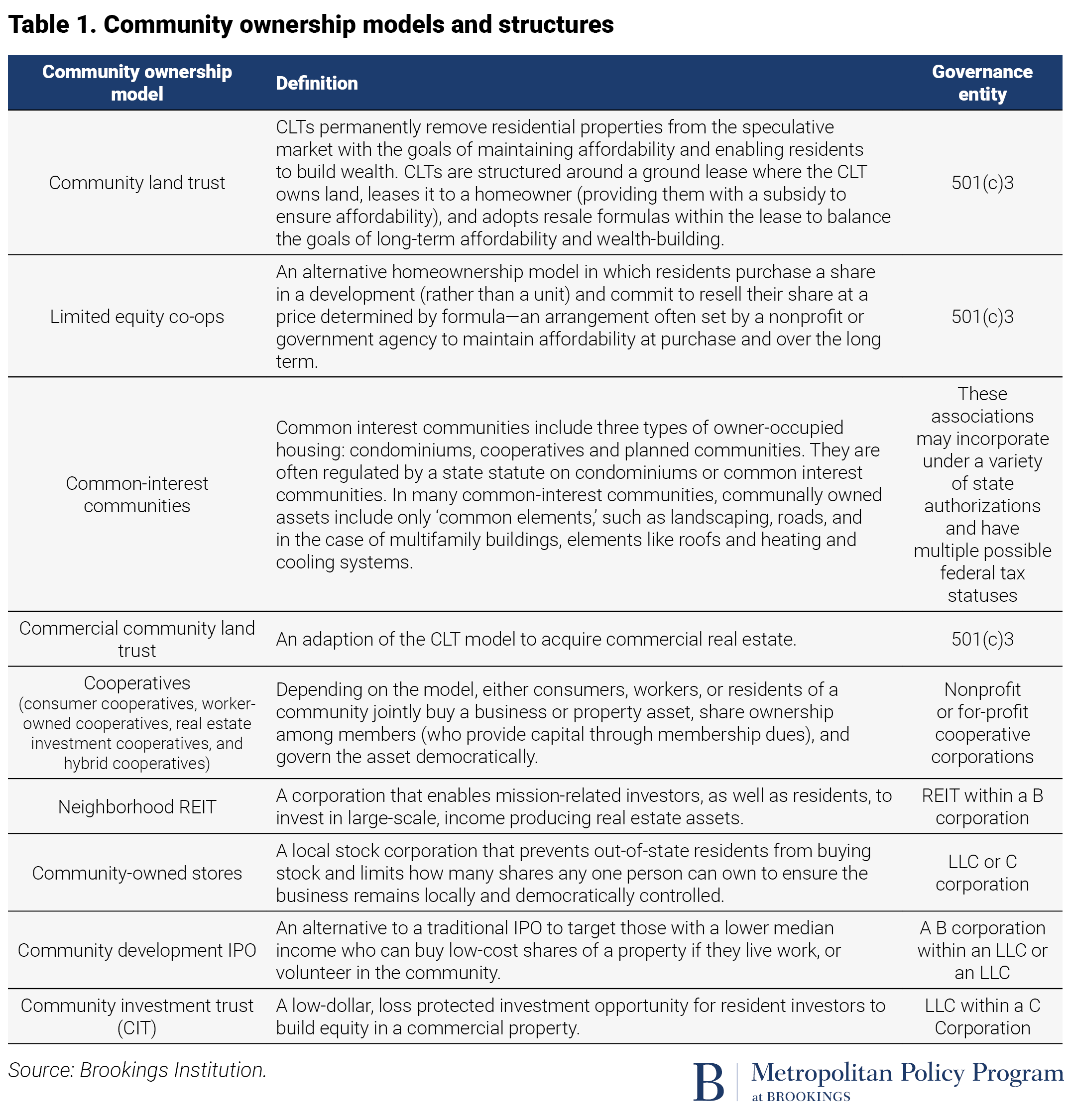

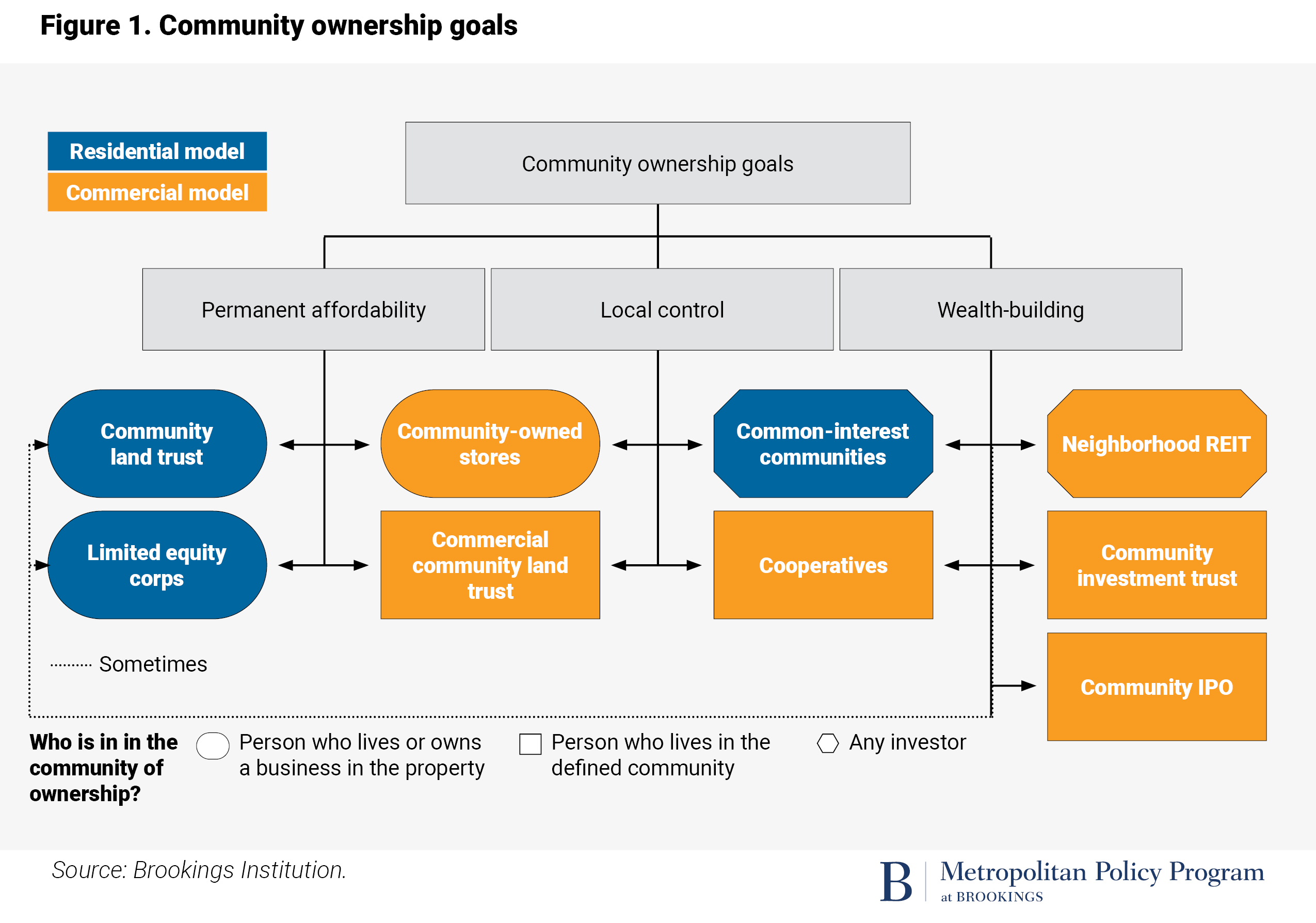

- What are the goals of community ownership? In the broadest terms, community ownership leverages property ownership for the “common good” of a defined community. What is meant by the “common good” varies based on the community, giving rise to many distinct community ownership models (Table 1) designed to achieve different goals, including preserving affordability, building wealth, and harnessing control of assets and neighborhood change (Figure 1). Some of these models are focused on owner-occupied residential property (housing), whereas others focus on those holding income-generating assets (commercial real estate, including multifamily rental housing).

- Who is the ‘community’ in community ownership? The definition of ‘community’ varies based on the model (Figure 1), but most models stipulate geographic boundaries which could be as large as a city, county, or state or as small as zip codes. Some models prioritize shares for residents with earnings below a certain percentage of the area median income.[8]

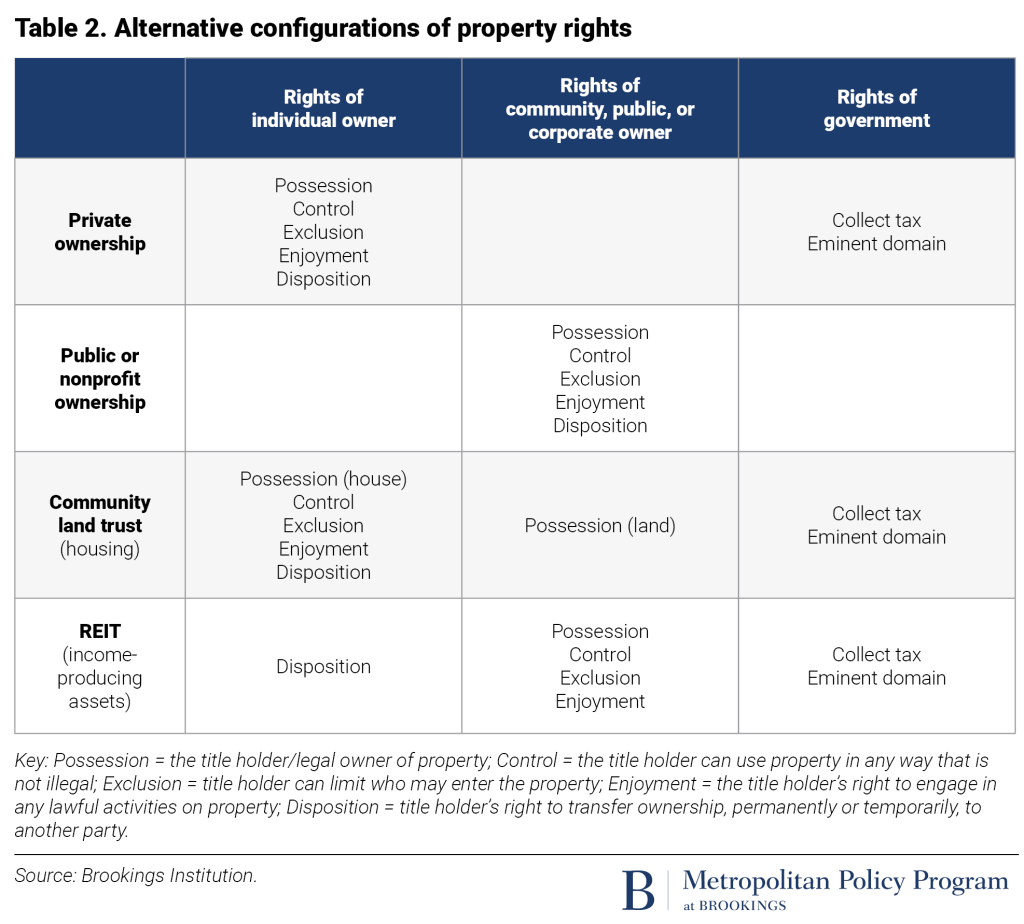

- Who ‘owns’ the property in community ownership? The legal owner also depends on the model (See “Possession” in Table 2). In some models, like Community Land Trusts (CLTs), ownership is divided between a nonprofit entity (who owns the land) and individuals within a community (who own the buildings on the land). In others, like REITs, the owner is a corporation and residents can become shareholders in the corporation to profit from development. In all cases, the key distinction is that individuals can earn, buy, or build their own equity while sharing control.

- How do individual wealth and community ownership intersect? Individuals do not give up all property rights when they enter a community of ownership. The mechanisms vary based on model (see Table 2), butin general, individuals and the community negotiate a set mechanism to share the benefits and obligations of ownership between individuals and the community. This mechanism then enables the community to pool resources—often using a system of shares. Shares belonging to individuals can then represent equity that can be grown, traded, or borrowed against, a right to collect shorter-term dividends (for properties generating income), and/or a proxy for share of control. Table 1 expands upon wealth-building components of each model.

Community ownership comes in various models and structures—with diverse goals, governance entities, and degrees of democratic decisionmaking. Table 1 defines common community ownership models and their associated governance entities; Figure 1 provides an overview of their differing motivations for benefiting a defined community.

In most models, community ownership is not just about changing who ‘owns’ buildings and land, but about a careful, partial redistribution of the property rights associated with owning assets and what is fundamentally meant by “ownership.”[9] Community ownership redistributes property rights so that individuals hold certain rights, while a community holds other rights[10] – influencing the degree to which collaborative decisionmaking about a property takes place, the activities that can occur within a property, how participants enter and exit the community of ownership, the structure of tax liability, and other rights associated with ownership (See Table 2).

Origins and evolution of community ownership

a) The decommodification of residential property

Community land trusts (CLTs) are one of the longest-standing and broadly applicable community ownership models, suitable for implementation in a range of urban and rural communities. They are not the most common form of community ownership in the United States (common-interest communities, which include homeowner’s associations and condominium associations, are), however CLTs provide useful grounding for understanding how many community ownership models differ from conventional ownership, and importantly, how they can be applied for community benefit and neighborhood revitalization.

The first CLT emerged during the Civil Rights struggle in the American South, when New Communities Incorporated formed in Lee County, Georgia in 1969 to help rural Black farmers secure land in the face of predatory lending, agricultural industrialization, and discrimination.[11] Until the 1980s, most CLTs were in rural areas to combat racist lending practices and the control of land by giant timber and agricultural corporations.[12] In the 1980s, the CLT model gained greater adoption in urban settings, with the goals of securing affordable homeownership and resisting gentrification.[13] A “third wave” of CLTs occurred during the housing boom of the 1990s, in which inflation and a strong economy prompted housing advocates to pursue new models for protecting affordability.[14]

Today, there are approximately 225 CLTs in the US, with the average CLT containing 50 housing units.[15] Most CLTs still target owner-occupied residential housing, yet there is growing recognition that homeownership is not the only model, nor necessarily the right model for every community. Communities need more than affordable housing to thrive; they need grocery stores, pharmacies, restaurants, and other small businesses to get their needs met.[16] For this reason, a ‘fourth wave’ of collective ownership is now underway, which expands shared ownership models to include income-generating real estate assets and innovative financing mechanisms to assemble capital for purchase, renovation, and maintenance of the property.[17]

b) Community ownership of commercial real estate and the ‘solidarity economy’

Two factors led to a greater interest in non-owner-occupied residential community ownership in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession. First, private equity groups, hedge funds, and institutional investors expanded their property portfolios to purchase single-family homes in bulk, leading to steep declines in homeownership (concentrated in select cities) and millions of low-income, predominantly minority families struggling with absentee landlords, poor property conditions, and rising property prices[18]. Second, economic inequality expanded within urban areas and across regions throughout and after the Recovery These factors prompted many residents to seek out commercial ownership models for more holistic neighborhood revitalization. These models can be useful tools in strong market neighborhoods (e.g. those with high rents, economic and population growth, and high demand for property) to empower tenants, ensure affordability for entrepreneurs, and retain local businesses and organizations who may otherwise be displaced.[19] In weak markets, they can increase residents’ access to much-needed amenities like grocery stores and retail establishments.[20] In all types of neighborhoods, they can support resident-led revitalization and community control.

Textbox 1: Expanding who can be an ‘investor’ in commercial real estate

Commercial community ownership models create accessible investment opportunities for low- and moderate-income people who may otherwise be excluded from commercial investment opportunities that require significant capital. For instance, 65% of American families invest in real estate by owning their own home, yet only 7% own at least some equity in commercial real estate.

Large commercial real estate assets are beyond the reach of many big investors, let alone low-dollar investors. Even aside from the purchase cost, the costs of the transaction itself to buy, or later to sell, are very high. Yet, the appeal of real estate remains that it offers a tangible wealth-building investment opportunity. The stock and bond markets are distant and opaque. Real estate is right there, but out of reach—without the right tools. Commercial community ownership models can create accessible, low-risk wealth-building for people and places.

While the rise in commercial community ownership models is still nascent, several models exist—all with the primary function of offering communities the opportunity to secure ownership of, or obtain shares in, a commercial real estate project to benefit from the asset.[21]

As commercial community ownership models become more common, many are aligning these models with the broader “solidarity economy” movement which positions itself as “sharing a broad set of values that stand in contrast to those of the dominant economy” including “building cultures and communities of cooperation and shared mechanisms of responsibility and democratic decisionmaking.”[22]

The fundamental question for these models is how they relate to city and regional market dynamics—most notably how they can co-exist in harmony with markets and avoid re-creating exclusionary patterns that disproportionately harm communities of color.[23] Additionally, there are market challenges to the viability of commercial community ownership models, as subsidies are available for creating and preserving affordable housing, but none exist for venturing into commercial properties.[24] Some of these questions are playing out in real time. An Urban Land Institute report found that community ownership models which charge below-market rent on a long-term basis for commercial properties can be seen as giving unfair advantage to tenants, yet, charging market rate is often seen as a conflict of interest for non-profits.[25] On the other hand, strictly financial investment models do not provide the opportunity for democratic control and local decisionmaking.[26]

Given these fundamental questions, we turn to the evidence base on the outcomes that shared ownership models can lead to, before turning to policy recommendations for how they can benefit the greatest number of people and places.

The evidence base for community ownership models: Economic, social, and civic benefits

Due to the fairly recent emergence of ownership models centered on commercial real estate, the research base on their effectiveness is underdeveloped. Much of the existing research focuses on residential CLTs, but the evidence base indicates that community land ownership models can lead to tangible economic, built environment, social, and civic benefits for a broad range of communities.

The economic benefits of community ownership:

Below are five key economic benefits supported by existing research:

- Community ownership can increase access to and retention of home ownership for low-income households: While limited to residential ownership models, the bulk of efficacy research on community ownership focuses on its effectiveness in helping low- and moderate-income households attain and retain homeownership.[27] For CLTs, in particular, their distinct value is in enhancing retention for homeownership, with more than 91% of low-income CLT homebuyers retaining homeownership after five years compared to 50% of other low-income first-time homebuyers, which enables them to have greater potential to realize a return on their real estate investment.[28]

- Community ownership can help homeowners better withstand economic shock: The Great Recession revealed the precarity of personal wealth embedded in residential real estate, but re-sale restricted homes (such as those in CLTs) experiences rates of default and foreclosure as low as a tenth of the rate reported by the owners of market-rate homes.[29] Researchers presume this is because CLTs have a third party that stand between them and lenders, review and approve proposed mortgages to prevent predatory terms, and intervene should the owners get behind in their payments—thereby reducing mortgage foreclosure and preventing the loss of household wealth.[30] In addition, because the mortgage encumbers only a house and not land, and the home price is below market, a market crash is less likely to put the owner underwater.[31] Finally, neighborhood trusts can enable communities to invest assets to create an endowment designed to help them weather economic downturns.[32]

- Community ownership can help close the racial wealth gap by distributing land-based wealth intergenerationally: A robust body of research demonstrates that the racial wealth gap can be partially attributed to low levels of real estate ownership and significant undervaluation of assets—including housing and businesses—in predominantly Black communities.[33] Community ownership models are a promising mechanism to close this gap, as community land trusts, in particular, have been shown to be successful in distributing land-based wealth intergenerationally.[34] There is a “trade-off” between wealth-building and affordability goals within CLTs, however; by separating housing value and land value, CLTs prevent land speculation, but this also means that the resident owner’s potential wealth gain is limited to equity in the house itself. Other community ownership models are more strictly focused on wealth creation and do not include tradeoffs for current owners that ensure affordability for future owners.

- Community ownership can increase access to amenities and support the growth of locally owned small businesses: Residents of low-income, majority-minority communities have less access to major grocers than those living in higher-income neighborhoods, which contributes to relatively higher grocery costs. Retail establishments in general are significantly underrepresented in Black communities, regardless of median income levels.[35] In communities where high real estate values or rents are prohibitive to small start-up businesses, community ownership models reduce this barrier to entry by preserving low-cost retail spaces.[36] In weaker markets, community ownership models bring overdue capital investments into communities to address commercial needs.[37] Commercial CLTs, in particular, have been found to catalyze additional commercial investments by the private market through illustrating the viability of commercial ventures in underinvested neighborhoods.[38] These benefits reach more than just the small business owners and their customers, as compared to absentee-owned businesses, locally owned businesses spend more money locally, imparting a “multiplier effect” in which the more times a dollar circulates in a community, the more income, wealth, and jobs that community enjoys. Indeed research demonstrates that the percentage of employment provided by locally owned businesses has a positive effect on county income and employment growth and a significant negative effect on poverty.[39]

- Community ownership can bring fiscal benefits to state and local governments in weaker markets: In many underinvested communities, high commercial vacancy rates and distressed assets destabilize the tax base by undermining commercial property values and limiting the success of other businesses in the area. These challenges can reduce sales tax revenue and undermine the fiscal stability needed to make investments (infrastructure or otherwise) that help communities thrive. Commercial community land ownership models, if applied in the context of rehabilitating distressed, vacant, or tax-delinquent assets, can have fiscal benefits by reducing vacancies, strengthening ‘community curb appeal’, making efficient use of infrastructure, and inducing demand for some kinds of services.[40]

The built environment benefits of community ownership:

Community ownership models also yield improvements to communities’ built environments, health, and resiliency. Residential models address housing insecurity by increasing the supply of affordable housing within the area, whereas commercial models can address vacancies that threaten community vitality.[41] Community ownership models have also long been used to support agriculture and farming to increase access to healthy and fresh food—helping food-insecure communities obtain agricultural land, programmatic support, and the means to control their own engage in food production.[42] Moreover, community ownership models often involve increasing access to community-serving amenities, like parks and community gardens.[43] Finally, community ownership can advance climate resiliency solutions for vulnerable communities, as residential ownership models provide typically cost-burdened households with the support to take on costs to mitigate extreme weather risks through weatherization, floodproofing, or air conditioning.[44]

The civic benefits of community ownership:

Community ownership models can also bolster civic capacity, as all models require the creation of a community-based ownership entity empowered to make decisions about the “common good” [45]— enabling communities to become stewards of important civic assets like parks and community centers.[46] These place-based entities can then also inspire residents to organize around other collective visions and goals, such as local housing and land use policy, infrastructure, public spaces, health and wellness, and other goals that will help communities thrive.[47] Finally, community ownership models help create “new cross-sector problem-solving tables” that enable community leaders to engage with public and private-sector stakeholders on issues of land use, development, and community benefit.[48] These models require investing heavily in capacity-building at the community level to support these civic actions. This investment, however, benefits not just the community ownership project or model, but the community as a whole. The reason some places are underserved is not just because of limits to supply or access to capital, but barriers in how communities deploy capital.[49] Community ownership models are a form of financial infrastructure than can increase the “capital absorption” capacity of a place.[50]

The social benefits of community ownership:

The social benefits of community ownership are harder to measure, which in no way diminishes their significance. Sociologists have long focused on the sense of loss that residents may feel if commercial development caters exclusively to new, typically higher-income, households.[51] Additionally, if displacement causes communities to lose their “social infrastructure,” including corner stores, barbershops, churches and long-standing small businesses that provide places for residents to gather, the sense of community loss and identity is palpable.[52] Commercial community ownership models can help combat this loss by offering neighborhoods control over their community assets so that long-time residents can advocate for development, while retaining long-standing cornerstones that reflect community history and identity.[53] In his case study of the Village at Market Creek, Rios (2013) found that negotiations over the commercial property created a new physical and political space to bridge differences and share power across diverse residents—becoming an important location for cross-cultural exchange, where negotiations of belonging, ownership, and, ultimately, power resulted in cooperative ownership of the commercial plaza.[54]

What barriers exist to scaling community ownership in more places?

Given the many benefits of community ownership, a logical question arises: Why aren’t communities everywhere implementing them? The answer is that considerable policy and structural barriers persist to launching successful community ownership nationwide. These barriers include:

- Access to capital: Real estate is a field with high barriers to entry, in large part, because most real estate deals require large amounts of up-front liquid capital. For most people and businesses across the income spectrum, their money is tied up in one thing or another— whether living/operating expenses, debt, retirement or college savings, or other investments. The new buyer of a real estate asset must assemble enough capital to finance not just the purchase, but likely also demolition/construction or rehabilitation, and sufficient funds to cover taxes and operating costs until the property can be inhabited or returned to income-generating use—a barrier which is prohibitive to many. Few subsidies exist to advance community ownership models, at times requiring development efforts to raise significant funds from philanthropy.

- Mission-driven investment models can be incompatible with the pace of real estate deals: A typical commercial real estate sales transaction might involve seven days of due diligence and 21 days from contract to close. The right opportunity for a community acquisition can easily be lost while assembling a capital stack from sources that are not built to move quickly.

- The organizing and access needed to move from ‘community’ to ‘community ownership’: While both community organizing and community ownership are motivated by the desire to make impactful and systemic change, the strategies, tactics, and vocabulary of activists/advocates and investors differ. In community ownership, advocates become investors, which involves learning new terminology, timelines, and tools—much of which requires access to “experts” and institutions.

- Lack of authorizing legislation for community ownership: While community land trusts are defined in federal law, newer innovative financial models for commercial community ownership, such as the neighborhood REIT, the community investment trust (CIT), and the community IPO are subject to state regulation of corporations and/or regulation by the U.S. government’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which regulates all tradable financial assets, and restricts participation in private corporations or funds to accredited investors. This regulation is to protect investors but the structural, review, and reporting requirements are substantial and require significant expertise. In this sense, community ownership is already available through LLCs and REITs to accredited investors, and a widespread norm in commercial real estate, but not to ordinary people. Formalizing these newer and innovative ownership models and streamlining requirements through legislative or regulatory action could dramatically facilitate the scaling of these models.

- Structural racism: The same systemic issues that motivate community ownership models are also obstacles to their creation and sustainability. The capital, real estate and legal expertise, and property assets required to be successful in community ownership efforts are largely not controlled by the marginalized communities. Even mission- or impact-driven actors, such as philanthropy, are largely risk-averse, prefer to support established models, and unprepared to confront the many explicit and implicit ways in which people of color, and especially Black people, are coded as risk or subject to novel rules and requirements. For example, the legal and explicitly racist practice of ‘grandfathering,’ whereby a long-standing property owner is exempt from modern zoning and code requirements, is widespread in real estate. However, when a property changes ownership, these violations must be resolved and brought into compliance—a burden that falls on the new owner.

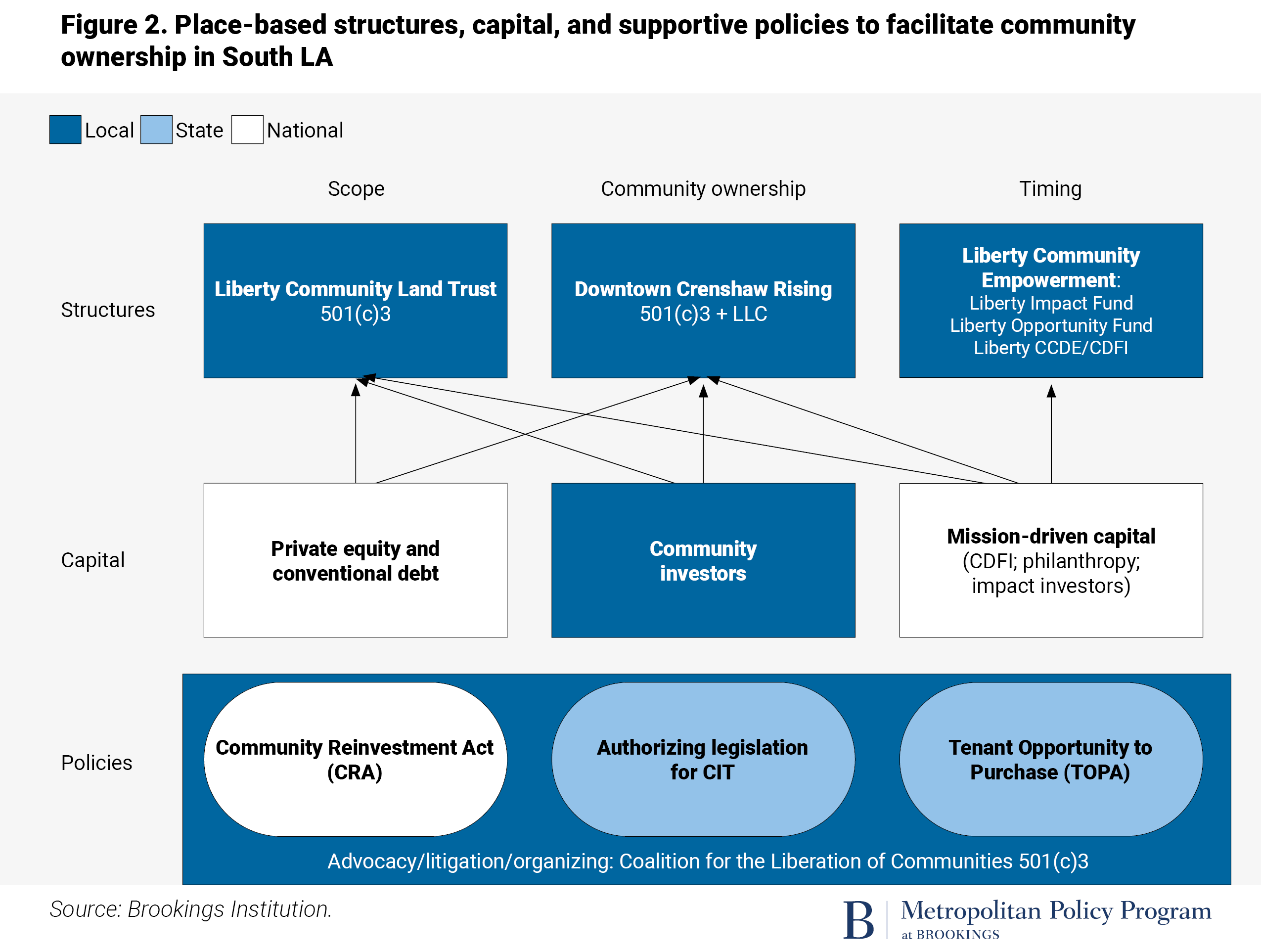

While many community ownership solutions are project-based, for example tied to a specific piece of real estate, the motivation to replace speculation with community stability and control is both people- and place-based. One deal, even a big one, does not change everything. It takes an ecosystem of structures, capital, and policies to create a foundation for prosperity in the wake of systemic disinvestment (See Textbox 2).

Textbox 2. Creating a community ownership ecosystem in South LA

Community organizers in Crenshaw are encountering these barriers to community ownership as they seek to purchase the Crenshaw Plaza mall. To address them, they are taking steps to build a network of place-based structures supported by a mix of capital from traditional and creative sources, while advocating for foundational policies to undergird these efforts in South LA and elsewhere (See Figure 2). Downtown Crenshaw Rising and the Liberty Community Land Trust are long-term structures for community ownership, while Liberty Community Empowerment includes various structures to receive and hold capital for purchase opportunities and ‘bank’ properties in trust for transfer to community ownership. The right policy reforms could maximize these structures’ reach, impact, and scalability to other places.

Conclusion

The market disruptions wrought by COVID-19 are only shining light on a system of property ownership long-designed to fail low-income people and people of color. With skyrocketing home prices in urban and rural places alike, a looming eviction crisis, and an uneven small business crisis, community ownership offers a critical solution to protect communities against these trends. Community ownership models equip communities with the tools to fight back against Wall Street’s efforts to buy Main Street, to protect vulnerable renters and owners in a period of extreme economic instability, ensure affordability, cultivate a viable small business ecosystem, and foster more resilient and equitable community-led recovery.

And there is an important role for policymakers across levels of governance to play in facilitating these goals. Local governments that deploy land banks to rehabilitate their property tax bases or have discretionary funding can connect these efforts to community ownership. State government agencies—including departments of commerce or economic development—can use their power, leverage, and resources to authorize legislation that supports the development community ownership models. The federal government too, can partner with state and local governments to facilitate the local ownership of real estate—which could include establishing and capitalizing state revolving loan funds to provide direct seed funding to locally- managed neighborhood investment funds. There is also an opportunity for local leaders to use American Rescue Plan funds to support community ownership.

As cities and regions seek to rebuild more equitably, it is critical to keep in mind what an community organizer for the Crenshaw Baldwin Hills-Crenshaw Plaza Mall told us, “This isn’t about a mall. It’s a community fighting for self-reliance, self-determination, and sustainability.” By supporting community-led efforts to own property and shape the forces of development in their own neighborhoods, cities have a simple but transformative opportunity to rewrite a system of land ownership that has been systematically failing too many people and places for far too long.

The authors thank Elwood Hopkins, Sheila Foster, Damien Goodmon, Daniel Fireside, Devin Culbertson, Brett Theodos, and Jennifer S. Vey for their review of various drafts of this piece. Any errors that remain are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Photos courtesy of Downtown Crenshaw Rising.

Endnotes

[1] Community Ownership as a Pathway to “Build Back Better.” SPARCC, n.d.: https://www.sparcchub.org/2021/04/08/community-ownership-as-a-pathway-to-build-back-better/; Perry, Andre, Jonathan Rothwell, and David Harshbarger. “The devaluation of assets in Black neighborhoods: The case of residential property.” Brookings Institution, November 2018: http://www.brookings.edu/research/devaluation-of-assets-in-black-neighborhoods/.

[2] Asset poverty is when households lack sufficient resources to provide for family members’ basic needs for a period of three months.

[3] Loh, Tracy Hadden and Andre M. Perry. “The real estate industry is divesting from Donald Trump—but divesting from white supremacy requires more.” Brookings Institution, February 2021: http://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/02/11/the-real-estate-industry-is-divesting-from-donald-trump-but-divesting-from-white-supremacy-requires-more/.; Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz. “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment.” American Economic Review 106, no. 4 (April 1, 2016): 855–902.; Case Study: The Community Investment Trust.” Mercy Corps, December 2019: https://www.mercycorps.org/research-resources/community-investment-trust-case-study.

[4] Agyeman, Julian and Kofi Boone, “Land loss has plagued black America since emancipation – is it time to look again at ‘black commons’ and collective ownership?” The Conversation, June 18, 2020: https://theconversation.com/land-loss-has-plagued-black-america-since-emancipation-is-it-time-to-look-again-at-black-commons-and-collective-ownership-140514.

[5] Individuals in community ownership models do not always legally ‘own’ their property, but rather have the rights to occupy, use, and enjoy, as well as obtain limited equity to share in the land value capture that the trust owns (See Table 2). The trust is often the legal ‘owner,’ with the community governing and stewarding the land with distinct property rights associated. For legal accuracy, some prefer the term “community control” over “community ownership”.

[6] Community Ownership as a Pathway to “Build Back Better.” SPARCC, n.d.: https://www.sparcchub.org/2021/04/08/community-ownership-as-a-pathway-to-build-back-better/

[7] Axel-Lute, “What Does “Community Control of Land” Mean?,” Shelterforce, May 2018: https://shelterforce.org/2018/05/08/what-does-community-control-of-land-mean/

[8] Theodos, Brett and Leiha Edmonds, “New models for Community Shareholding: Equity investing in neighborhood real estate investment trusts and cooperatives.” Urban Institute: December 2020: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103341/new-models-for-community-shareholding_0.pdf.

[9] Dub, Steve. “Ownership as Social Relation: Nonprofit Strategies to Build Community Wealth through Land.” Nonprofit Quarterly, December 2018: https://nonprofitquarterly.org/ownership-as-social-relation-nonprofit-strategies-to-build-community-wealth-through-land/.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Davis, John, “The Community Land Trust Reader,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/the-community-land-trust-reader-chp.pdf. Davis, John. “Origins and Evolution of the Community Land Trust in the United States.” (Burlington Associates in Community Development LLC ,2014: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-davis14.pdf.; Rosenberg, Greg and Jeffrey Yuen, “Beyond Housing: Urban Agriculture and Commercial Development by Community Land Trusts.” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2012: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-rosenburg-yuen.pdf

[12] Davis, John. “Origins and Evolution of the Community Land Trust in the United States.” (Burlington Associates in Community Development LLC ,2014: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-davis14.pdf.

[13] Rosenberg, Greg and Jeffrey Yuen, “Beyond Housing: Urban Agriculture and Commercial Development by Community Land Trusts.” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2012: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-rosenburg-yuen.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Greenberg, David, “Community Land Trusts and Community Development: Partners against displacement,” LISC, February 2019.

[16] Margulies, Joseph. “Communities need neighborhood trusts.” Stanford Social Innovation Review: Spring 2019.

[17] Across all ‘waves’ of community ownership, trusts have been used to support urban agriculture and farming to increase access to healthy and fresh food. CLTs were created to address agricultural land ownership in Georgia in the 1960s and have been used since then to secure access to agricultural land, provide programmatic support, and directly engage in food production.

[18] Loh, Tracy Hadden, Christopher Coes, and Becca Buthe. “Separate and unequal: Persistent residential segregation is sustaining racial and economic injustice in the U.S.” Brookings Institution, December 2020: http://www.brookings.edu/essay/trend-1-separate-and-unequal-neighborhoods-are-sustaining-racial-and-economic-injustice-in-the-us/. Abrams, Amanda, “Lessons from the last housing crisis: How to get control of properties.” Shelterforce, September 2020: https://shelterforce.org/2020/09/17/lessons-from-the-last-housing-crisis/

[19] All-in Cities, “Commercial community land trusts,” PolicyLink: https://allincities.org/toolkit/commercial-community-land-trusts.

[20] Vey, Jennifer S., Tracy Hadden Loh, and Elwood Hopkins, “A new place-based federal initiative for empowering local real estate ownership.” Brookings Institution, December 16, 2020: http://www.brookings.edu/research/a-new-place-based-federal-initiative-for-empowering-local-real-estate-ownership/.

[21] Theodos, Brett and Leiha Edmonds, “New models for Community Shareholding: Equity investing in neighborhood real estate investment trusts and cooperatives.” Urban Institute: December 2020: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103341/new-models-for-community-shareholding_0.pdf.

[22] Miller, Ethan. Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues. Solidarity economy I: Building alternatives for people and planet (2010): 25-41.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Nicoel Martinez, “CLTs still going commercial – Nonprofit offices, hairdressers, and a sausage factory.” Shelterforce: April 5, 2021: https://shelterforce.org/2021/04/05/clts-still-going-commercial-nonprofit-offices-hairdressers-and-sausage/.

[25] Brown, Emily and Ted Ranney, “Community Land Trusts and Commercial Properties: A Social Justice Committee Report for the Urban Land Institute Technical Assistance Program for Atlanta Land Trust Collaborative,” nd: https://pdfslide.us/documents/commercial-community-land-trusts.html

[26] Theodos, Brett and Leiha Edmonds, “New models for Community Shareholding: Equity investing in neighborhood real estate investment trusts and cooperatives.” Urban Institute: December 2020: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103341/new-models-for-community-shareholding_0.pdf.

[27] Sorce, Elizabeth. The Role of Community Land Trusts in Preserving and Creating Commercial Assets: A Dual Case Study of Rondo CLT in St. Paul, Minnesota and Crescent City CLT in New Orleans, Louisiana. University of New Orleans Dissertations and Theses: 2012: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2558&context=td

[28] Ibid.

[29] Davis, John. “Common Ground: Community-owned land as a platform for equitable and sustainable development.” University of San Francisco Law Review, Vol 51: https://community-wealth.org/content/common-ground-community-owned-land-platform-equitable-and-sustainable-development

[30] Ibid.

[31] Fireside, Daniel. “Community land trust keeps prices affordable – for now and forever.” P. 342-352.in The Community Land Trust Reader, John Emmeus Davis, ed. Washington, DC: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2010: https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/the-community-land-trust-reader-chp.pdf

[32] Margulies, Joseph. “Communities need neighborhood trusts.” Stanford Social Innovation Review: Spring 2019.

[33] Hopkins, Elwood, Jennifer S. Vey, and Tracy Hadden Loh, “How states can empower local ownership for a just recovery.” Brookings Institution, July 23, 2020: http://www.brookings.edu/research/how-states-can-empower-local-ownership-for-a-just-recovery/.

[34] Davis, John. “Common Ground: Community-owned land as a platform for equitable and sustainable development.” University of San Francisco Law Review, Vol 51: https://community-wealth.org/content/common-ground-community-owned-land-platform-equitable-and-sustainable-development

[35] Rowlands, D. W. and Tracy Hadden Loh, “Retail revolution: The new rules of retail call for small business empowerment.” Brookings Institution, December 16, 2020: http://www.brookings.edu/essay/trend-5-the-new-rules-of-retail-call-for-local-small-business-empowerment/.

[36] Sorce, Elizabeth. The Role of Community Land Trusts in Preserving and Creating Commercial Assets: A Dual Case Study of Rondo CLT in St. Paul, Minnesota and Crescent City CLT in New Orleans, Louisiana. University of New Orleans Dissertations and Theses: 2012: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2558&context=td

[37] Rosenberg, Greg and Jeffrey Yuen, “Beyond Housing: Urban Agriculture and Commercial Development by Community Land Trusts.” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2012: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-rosenburg-yuen.pdf

[38] Ibid.

[39] Beckon, Brian, Amy Cortese, Janice Shade, and Michael Shuman, “Community investment funds: A how-to guide for building local wealth, equity, and justice.” A Publication of the National Coalition for Community Capital and the Solidago Foundation, nd

[40] Vey, Jennifer S., Tracy Hadden Loh, and Elwood Hopkins, “A new place-based federal initiative for empowering local real estate ownership.” Brookings Institution, December 16, 2020: http://www.brookings.edu/research/a-new-place-based-federal-initiative-for-empowering-local-real-estate-ownership/.

[41] Grannis, Jessica. “Community Land = Community Resilience.” Georgetown Climate Center, January 2021: https://www.georgetownclimate.org/files/report/Community_Land_Trust_Report_2021.pdf.

[42] Yuen, Jeffrey. City Farms on CLTs: How Community Land Trusts Are Supporting Urban Agriculture.” Lincoln Institute, April 2014: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/city-farms-clts.

[43] Grannis, Jessica. “Community Land = Community Resilience.” Georgetown Climate Center, January 2021: https://www.georgetownclimate.org/files/report/Community_Land_Trust_Report_2021.pdf.

[45] Davis, John. “Common Ground: Community-owned land as a platform for equitable and sustainable development.” University of San Francisco Law Review, Vol 51:

[46] Grannis, Jessica. “Community Land = Community Resilience.” Georgetown Climate Center, January 2021: https://www.georgetownclimate.org/files/report/Community_Land_Trust_Report_2021.pdf.

[47] Greenberg, David, “Community Land Trusts and Community Development: Partners against displacement,” LISC, February 2019. Vey, Jennifer S., Tracy Hadden Loh, and Elwood Hopkins, “A new place-based federal initiative for empowering local real estate ownership.” Brookings Institution, December 16, 2020: http://www.brookings.edu/research/a-new-place-based-federal-initiative-for-empowering-local-real-estate-ownership/.

[48] American Cities, “Neighborhood Investment Trusts are promising wealth-building models for residents in revitalizing communities.” The Kresge Foundation: February 8, 2021: https://kresge.org/news-views/neighborhood-investment-trusts-are-promising-wealth-building-models-for-residents-in-revitalizing-communities/.

[49] Wood, D., K. Grace, and R. Hacke. “The capital absorption capacity of places.” Initiative for Responsible Investment at the Harvard Kennedy School and Living Cities: https://iri.hks.harvard.edu/files/iri/files/the_capital_absorption_capacity_of_places_2012.pdf

[50] Center for Community Investment, “New Tools: Diving into Shared Priorities, Pipeline, and Enabling Environment,” March 2019: https://centerforcommunityinvestment.org/blog/new-tools-diving-shared-priorities-pipeline-and-enabling-environment

[51] Zukin, S., Trujillo, V., Frase, P., Jackson, D., Recuber, T., & Walker, A. (2009). New retail capital and neighborhood change: Boutiques and gentrification in New York City. City & Community, 8(1), 47-64.

[52] Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Crown.

[53] Zukin, S., Trujillo, V., Frase, P., Jackson, D., Recuber, T., & Walker, A. (2009). New retail capital and neighborhood change: Boutiques and gentrification in New York City. City & Community, 8(1), 47-64.

[54] Rios, M. (2013). From a Neighborhood of Strangers to a Community of Fate: The Village at Market Creek Plaza. In Transcultural Cities: Border-Crossing and Placemaking ed. Hou, J. https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1fbDN68BuS9wCQMA2l_0XnJncDSBCSYSt